Fly presentation and drag-free drift

You've rigged up your rod, landed your cast in the right place, your fly is on the water...and, it's waterskiing. Tactics and tips to maintain a drag-free drift that's irresistible to fish.

Make friends with slack to fight the evil forces of drag. All about achieving the zen that is drag-free drift.

Inside this lesson

- In the beginning...a parable on Drift

- It's all about drag-free drift

- Recoginizing drag

- What does drag look like?

- How and why does drag happen?

- Is drag on your fly always bad?

- Techniques for achieving drag-free drift

- The importance of line management

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Bringing it all together

In the beginning...

In the beginning...there was DRIFT.

All was right in the world. Things moved at their own speed. Some fast, some slow.

All beings were connected to a central vibration, while acting of their own accord. FLOW was ever-present.

Playful ANGLERS roamed the land, frolicking with their fellow creatures, using rod and line.

Until the day one angler crossed an invisible barrier, and began to assert dominance over his fellow creatures. This angler started keeping score. And their paradise was forever changed.

A mighty disturbance crossed the land, bringing forth a strong force of disruption from flow. The world heralded the dark coming of wicked and vexatious DRAG.

Drag pulled everything false out of the flow, and flung the reality of their artifice back at the anglers. It showed the puppet strings, the falsity of even child-like endeavors to fool nature. Nature could no longer be fooled, even in fun. Lo, the anglers were sad.

After many years of frustration and question, one angler gave up. There was no hope. They threw it all away.

But all was not lost, because in throwing it all away they discovered SLACK. For the first time, the angler could cast and evade drag. It took a couple whiles to dial in just how much slack to apply, but for some reason just enough slack fooled drag, and allowed them to touch the flow that once was, and sometimes fool nature's swimming creatures.

This, cousin of flow, the angler named DRIFT. They began to spread the news of DRAG-FREE DRIFT to all who would listen, and see the wake-free flies floating along as if untethered.

They roamed the land, casting and telling their tale, to try and help all reach the exalted state experienced by anglers everywhere before the fall.

It's all about drag-free drift

To paraphrase football coach Red Sanders, In fly fishing, presentation isn't everything. It's the only thing.

It's not just about having the right gear or the perfect fly. It's about how you deliver that fly to the fish. If I could boil the entire Technique pillar down to one single concept to build skills around, it would be this one: drag-free drift.

If I could boil the entire Technique pillar down to one single concept to build skills around, it would be this one: drag-free drift.

Presentation is the direct interface we have between the fly and the fish. And drag-free drift is how, when fishing dry flies and nymphs, we try and make a realistic-enough imitation of nature for that fly to fool that fish.

Some anglers are especially interested in matching the hatch, and finding the right fly. Some are interested in crisp, long casts with perfect loops.

You don't need either of those to catch fish.

Sure, they help. But, what you do need, 90% of the time, is to achieve drag-free drift.

What does "the fly is fishing" mean?

There's a linguistically complex thing anglers say that can help you wrap your head around this broad concept of drag-free drift a bit. It's "the fly is fishing."

"Wait," your brain stops you, to think out loud. "The fly isn't fishing. I'm the one that's fishing. Me and my body." Yes, dear brain, that's true. But when your fly is dragging, or moving unnaturally in the water, it's not fishing. When it's just floating along, in a manner that fish will see as neutral and natural, it is.

This is the case whether you're dry fly fishing or nymphing or stripping streamers or swinging for steelhead. Sometimes that's a "dead drift" (e.g. zero drag) and sometimes that's artificial drag to initiate movement, like stripping a fly, or swinging a fly. If your fly isn't moving in the right manner, you're not going to be as effective at enticing a fish.

Achieving a drag-free drift is essential for fooling fish into thinking your fly is a natural insect, or other food item, if you're fishing a dead-drift streamer. Here's why it matters:

- Natural appearance: Fish are used to seeing food items (e.g. bugs) drift naturally with the current.

- Reduced suspicion: An unnatural drift alerts fish to the presence of something not like the others

- Increased strike likelihood: A drag-free drift coaxes the fish into trusting the food source.

Drag-free drift is our fly moving in a state of weightlessness, as if it's not attached to that piece of plastic running all the way back to a crafty(-ish) angler.

In our little parable above, we invented the arch-nemesis DRAG. Fly anglers have a bunch of different cryptonyms for our other arch-nemesis THE WIND (origin story to come) to avoid invoking it (the W, Walter, Uncle Gusty & Aunt Breezy), so why not personify drag-free drift? What would that Drag-Free Drifter be?

For some reason I'm imagining Wilford Brimley's face with his big mustache, just floating along out there, happy as, the Drag-Free Drifter, driftin' away.

(n.b. If you have any similar unhinged visions of who the Drag-free Drifter might be, leave a note in the comments.)

Recognizing drag

Just like unconscious bias, there's no way to eliminate drag. It will always be there. But the first step toward doing something about it is recognizing it happens.

What does drag look like?

If your rod tip is wiggling and the fly looks like its waterskiing (or wakeboarding, whichever you prefer), it's pretty clear your fly is dragging.

When the drag might be more subtle, there are a few signs you can look to:

- Your fly is moving faster or slower than surrounding debris or bubbles

- There are smaller disturbances or bulges of water around your fly

- You feel tension in your line, when the fly should be drifting freely

How and why does drag happen?

Fundamentally, drag happens when there's tension in the line between your rod and your fly.

The easiest way to initiate drag and get a sense of it, when you're on a river, is to cast upstream, then reach out, with your rod in your upstream arm, and point your rod directly upstream and hold it there.

Depending on how much line you have out, after a few seconds your fly should stop moving more or less in front of you. And, it'll start to pull on your rod tip, and a tiny wake will form around it. The current is trying to push it at $x$ miles per hour, and your rod tip is holding it in place at none miles per hour. $x-x=0$.

Any time you have a discrepancy in that equation, that is, any time your fly—dry fly or nymph—is moving at a different speed to the currents that surround it, you have some form of drag.

Drag will always happen. It will inevitably creep into our presentation system, because we have a fixed line and leader and fly. It's static. Our goal is to prolong the window of opportunity where the fly is presented drag-free over a holding lie, creating the longest possible drag-free drift to allow a fish to evaluate and commit to ingesting our offering.

There are a couple of layers of why drag happens. Here are a few causes of drag:

- Your fly is done fishing.

At the end of every drift, there's drag. It is inevitable. Drag is the signal to the angler to pick it up and cast again. You'll get the timing down to anticipate this and re-cast before drag sets in, to spend more time with your fly inside that window of opportunity. - Your cast and line maintenance was inadequate.

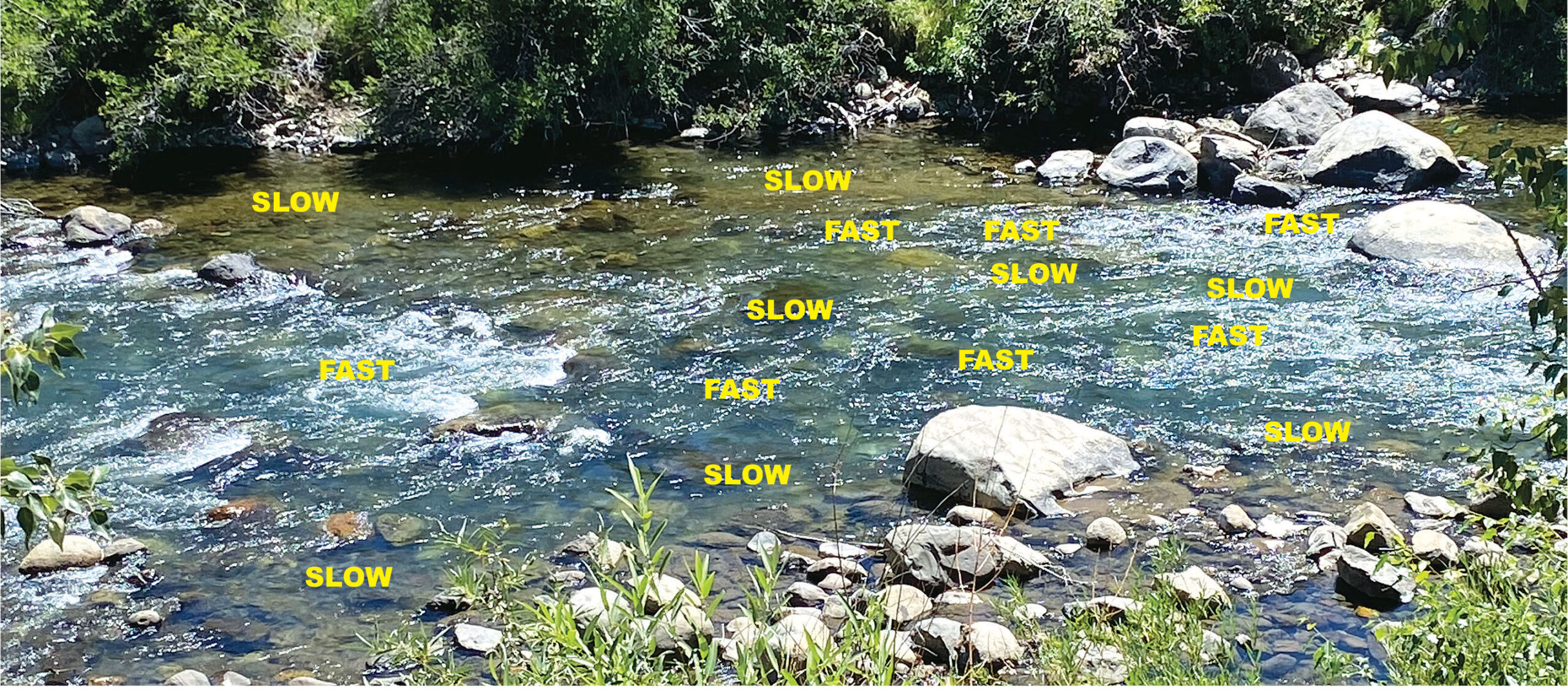

I know, tough to hear. But, the reason your fly is done fishing is because you haven't added or maintained the proper amount of slack in the system to cover the entire lie / run / area you surmise a fish to be waiting. Adding mends, or casting with the proper setup or aerial mends to allow for a longer drift are 201-level skills that you'll need to start to develop to keep that window of opportunity open as long as possible. - Water and how it behaves (its currents) are weird.

Obviously not a technical term, but us humans have a pretty simplistic understanding of how water behaves. Here's the most important thing, when it comes to fly-fishing: Water is not uniform. There are all sorts of variations, microcurrents, temperature changes, etc. as water moves across the various obstacles it encounters in a river or stream. Drag is always waiting somewhere.

If you're ever in a dry fly situation where currents are especially gnarly and you can't get a handle on whether your drift is drag-free or not, tie on a second dry fly off the bend of the hook in the first.

When the two flies are floating along at the same speed without any movement relative to each other (either up and down the river, or laterally) you're golden.

Then look for seams around the lie you're fishing where you can achieve that drag-free drift.

Is drag on your fly always bad?

Here's one more twist for your anchor rope: Drag on your fly isn't always bad. There are certain situation where we want drag. Hell, we try and induce and control it.

Two fly-fishing situations where drag is good:

- When you're swinging wet flies

- When you're stripping streamers

Let's start with wet flies. The traditional method of fishing wet flies, whether it's small soft hackle wets for trout, or larger flies for salmon and steelhead, is casting downstream and across at a ~45° angle. Our fly lays out in the water at that angle, then comes into tension with the rod, then swings across the area we're fishing.

The tension from our line is what activates the fly, and causes the feathers in the soft hackle to move, and create the insect imitation. Sure, you can dead-drift a wet fly, and it's sometimes effective, but it's a lot more effective when it's on the swing.

Same with swinging wet flies for steelhead. Steelhead aren't hungry; they strike with the same motivation that a cat will paw at one of those little feather balls on a stick, just out of sheer aggression. An undulating sub-surface fly under tension is what we use to get that done.

A streamer, meanwhile, is often stripped. Stripping a streamer means selectively pulling line in. The distance of each pull, the pattern, and rhythm, or lack thereof, the combination of lifting the rod tip, or moving the rod, are variable and part of the art of fishing streamers. These are all creating drag, using the water's current to induce fly movement.

Drag and fly design

For streamers and steelhead flies—understanding how the fly performs under drag, how it deforms and undulates when current is applied—is so important, there are specialized tools to study it.

One is what you might call a drag tank, or a fly testing tank. Here's one marketed by Flymen, a company that specializes in selling flies that feature a lot of movement, sometimes made possible through adding multiple articulated shanks and hooks into the mix.

The goal here is to test, visualize, and perfect how a fly fishes under various applications of current—drag—to find the most irresistible combination.

Techniques for achieving drag-free drift

If you can recall our parable, DRAG was ultimately foiled by the discovery of SLACK. It is slack, in our lines, in our system, that, in measured doses, allows us to counteract drag.

Reducing friction

If there's less material for current to grab, there's less drag. A couple easy fixes are:"

- Keep your rod tip up, and prevent too much line laying on the water. The current will create a "belly" on the line if the current near to you is stronger than the current far away.

- Fish with longer leaders. With less surface area, a leader drags less than a fly line.

Adding slack

Tension is the root cause of drag, and slack is the antidote. We can introduce it in a few different ways:

- Through the casting motion

- Once the fly is on the water

We introduce it with the cast, using reach casts, or aerial mends. In the reach cast, we move our arm to pre-position the line in the forward cast to land in a situation conducive to a longer drift. By laying our cast down against the flow of the current, more of the line is in a position with the current, and drag is limited. Here's what a reach cast looks like, from casting legend Carl McNeil at Epic:

In a pile cast, a style of slack line cast, we arrest the forward momentum of the cast, so the line falls in something resembling more of a pile, rather than a straight line. This allows the fly (or, fly and indicator, if you're fishing with a suspended rig) to begin to move as a unit, together, rather than in a more linear way.

These are more advanced, and fall under the heading of "aerial mends". The central concept is one of mending, and the easiest way to learn to mend is when your fly is on the water.

Mending your line

Mending, in one sense, fixes what is broken. In the fly-fishing sense, a mend is when you introduce slack to your drift to prolong it fishing.

The simplest way to do this is to throw in some slack. It's easier said than done, but this involves a wrist-y movement that simultaneously move the rod tip to reposition the fly line on the water, while releasing line with the hand, usually your off-hand, that you were using to bring in or pay out fly line during the drift.

Here's Orvis' Tom Rosenbauer breaking it down as simply as it can get:

We've talked about mending in some detail here, as well.

California Fly Fisher has a great mending primer, with some fun diagrams:

The importance of line management

Learning to cast a fly rod effectively is challenging. Probably the second-most-challenging technique we employ regularly (and the one beginning anglers have the most trouble with) is mending to manage your line.

I think of it almost like a shuffle. You're constantly trying to pay out a little more line to prolong your drift, to help keep the fly fishing longer, while not mending too hard and disturbing the fly's drift and scaring a fish away.

Properly executed, mends can pay out line continuously as the fly moves through the run.

Slack, with not so much slack that we lose control

There's a delicate balance here. If you have too much slack on the water at any given time, you won't be in touch with your fly.

It'll be tougher to set the hook effectively when you see a fish rise to your fly. You'll have to lift and take up all that slack off the water, and fight surface tension and the currents its moving through, to help the make contact with the fish's mouth.

Effective line management involves:

- Constantly adjusting your line position so your fly is drifting drag-free

- Stripping in or feeding out line as needed to account for the current

- Being aware of different current seams across the river, both behind and in front of your fly and line

It takes practice, and perseverance.

The mantra continues to be, as told to me by a sage guide, "If you can manage your line, you can manage your life."

That means keeping your back cast out of bushes, and not getting your free line tangled at your knees if you're wading, or in the boat, but above all, on the water.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Here are some common questions folks have asked about achieving drag-free drift, both in class, and generally.

How can I tell if my fly is drifting naturally?

One way to think about that is getting relative motion to things that are floating along the river. Foam lines, bubbles, flotsam, things fo that nature. If your fly is floating along with them relatively the same speed, moving at the speed of the river, that's probably experiencing drag-free drift.

Is presentation just a dry fly thing?

Presentation is most important for dry fly fishing, but in any fishing scenario you're going to want to be able to visualize how your fly is behaving with regard to the river.

How can I improve my line management skills?

Practice is key. Spend some time on the water focusing specifically on line management. Pay attention to how currents affect your line and experiment with different mending techniques until you get the feel for how to add line without moving your fly. An indicator is a helpful tool to practice with; it has more surface tension, so it's easier to mend and without disturbing it. As you're learning it's not a terrible idea to add an indicator in addition to a dry fly, to practice mending and not moving the indicator. As you get the hang of it, you'll be able to up the challenge level by taking off the indicator.

Does the type of line I use affect my ability to achieve a drag-free drift?

If you're using a weight-forward (WF) floating line, the most versatile fly line, there's going to be more of the line on the water than if you're using a double-taper (DT) line, so the fly line will be more conducive to drag, and harder to mend. But, for a beginner, it's easier to cast with a weight-forward fly line than a double-taper if you're starting out. So, stick with the WF until you're starting to feel confident in your cast, then try a DT, that can offer a more delicate presentation.

Got any other questions?

Throw 'em in the comments!

Bringing it all together

Presenting the fly in the right way, and achieving drag-free drift, is skill that takes years to develop confidence in. It requires practice, observation, and constant adaptation to what the river wants us to do. Eventually, it will become second nature, something you do automatically.

Until then, we're lucky that fish aren't always as canny as we give them credit for. You'll catch fish on flies that are dragging. You'll miss strikes, but hook the fish anyway despite sketchy presentations. You'll look down from spotting a lovely Lazuli Bunting and realize you have a fish on.

But as you progress, you'll find yourself positioning your fly for success more and more effectively.