Thinking in watersheds

Understanding watersheds, and the different types of rivers we're going to encounter when fly-fishing

Inside this entry:

What is a watershed?

What makes up a watershed?

Types of rivers in watersheds

Freestone rivers

Tailwaters

Spring creeks

Spotlight on the Clackamas watershed

Summing up

On fly-fishing environments

Zooming in from the macro to understand how different kinds of rivers support different populations of fish an types of fishing, and how everything's connected together.

On our journey to understand where fish—specifically trout—live, our first major concepts are watersheds and river types.

We're approaching these elements from the macro to the micro, which always calls to mind an old film called Powers of 10. It's a film created by the office of two famous designers—Ray and Charles Eames—for IBM, to illustrate understanding at various scales.

If you've never seen it, it's worth watching:

Powers of 10, fly-fishing edition

If we were to remake the film for our own purposes, we'd maybe start with the hungry trout. Zooming out, we'd see its picnic blanket, the lie where it stalks its lunch.

One step further, we'd see the river features, the neighborhood it frequents. Zooming back more, we'd see the type of river it lives in. And, one further step out, the watershed.

When we zoom in past the trout, we might see other river creatures, aquatic insects, microorganisms, and the composition of the water in any given stream or river.

So, there's a lot to see. Let's get on with it:

What is a watershed?

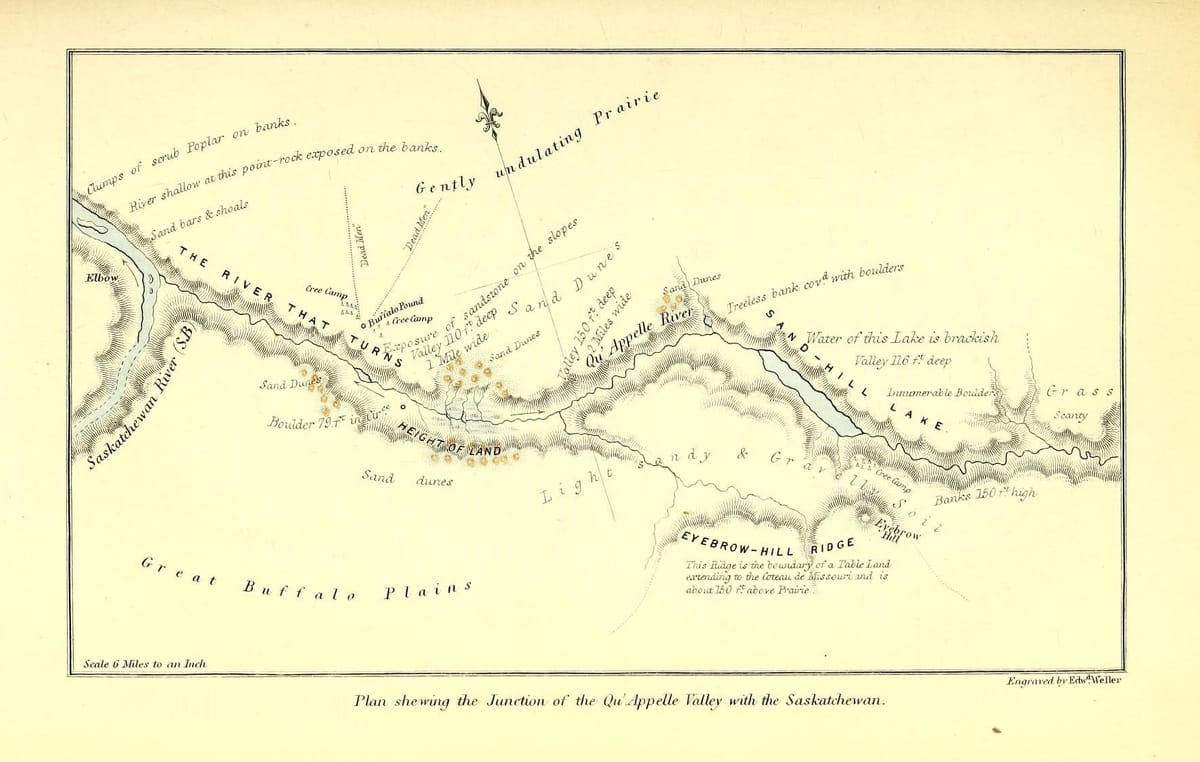

If you're thinking like a hydrologist, you can divide any terrain up into watersheds. Even deserts. All rivers exist as part of a watershed, a compilation of similar features in a common catchment area.

If you were to go to the continental divide of the United States of America, as it runs south through Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico. and take an eyedropper and drop a single drop of water, hydrologically speaking, it would go one of two directions. It would probably go east into the Mighty Mississippi, or west probably into the Colorado, or the Columbia.

Here's a great visual:

Watersheds are, to put it exceptionally simply, a continued smaller variation on this one idea. Water is going to drain somewhere. The conservation mantra "we're all downstream" takes root in this idea.

What makes up a watershed?

Most of what we know and think about rivers happens more localized, identifiable watersheds.

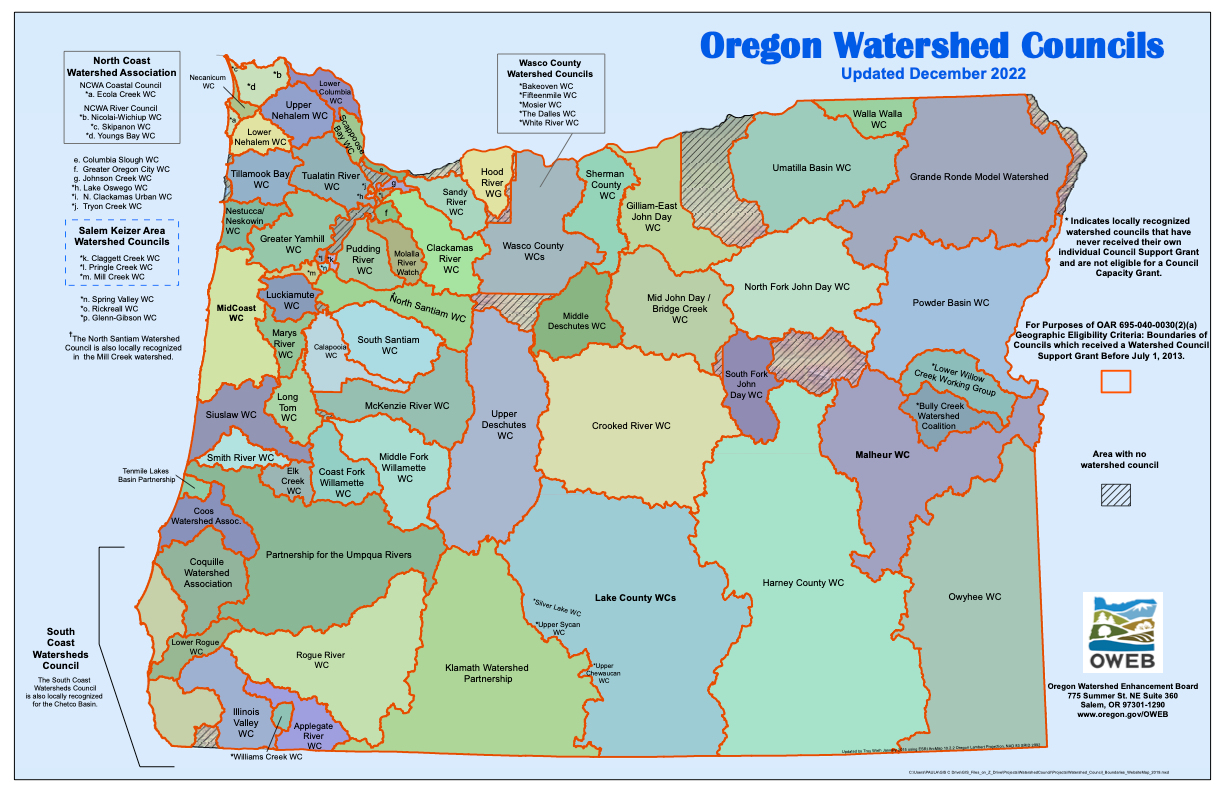

Since the 1990s, here in Oregon, communities have organized around Watershed Councils to represent local interest to government and policymakers. There are even parallel activist groups. For instance, here in the top left we've got the North Coast Watershed Association, and its activist counterpart the North Coast Communities for Watershed Protection. Sometimes these comprise whole watersheds, sometimes partial watersheds, but they're a good level of organization to feature in our Powers of 10-type journey.

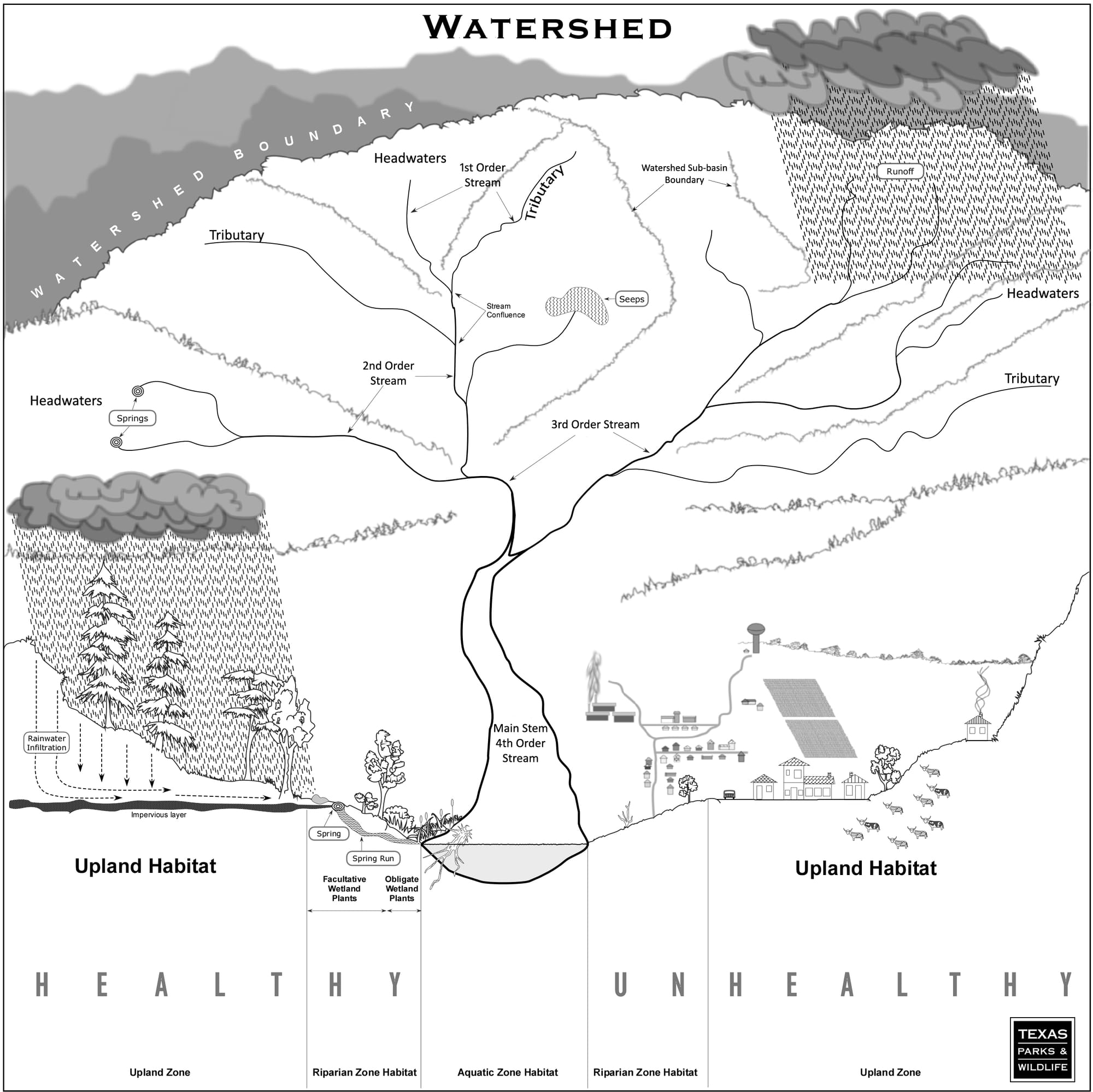

Terrain, altitude and gravity are the primary designators of a watershed. What flows where. Any given watershed has its the apex, a headwaters, where things start. Sometimes headwaters are glaciated, meaning a big, old accumulation of snow and ice has a seasonal freeze and thaw cycle that creates a river. Sometimes the headwaters are formed by an underground spring. Sometimes they're formed by rainwater.

As water tumbles down from the headwaters, it may not really be enough to be considered a river, until it's joined by other tributaries. Similar watercourses, maybe other creeks and seeps, join at confluences, and a river becomes larger.

Ultimately the water arrives in cultivated areas, where we use it: in agriculture to water crops and for animals, for ourselves, to drink and bathe and process our sewage, in industry, to cool the massive computers that mine bitcoin or data centers hosting thousands of our cat photos.

Our river ultimately flows out to the ocean, and inevitably is evaporated again to come down somewhere else as rain.

A water molecule sees a lot of change in a short period of time. As long as its not trapped in an ice sheet for centuries.

Types of rivers in watersheds

Inside that watershed, we have different kinds of rivers as well. There are the main categorizations you should know.

Freestone rivers

A freestone river is a river what you'd most traditionally consider a river. It starts at the top of a mountain, usually in a glacier or a snowfield and comes down, gathering momentum, getting larger, and eventually rolling into another river, or the sea.

The key feature of a freestone river—somewhat uncommon in modern society—is that it's unfettered by a dam from its source. So for instance, the John Day, a famous freestone river. The John Day runs high when it's melt season, and by the end of August, it's super low. It's entirely fed by glacial snow melt.

The John Day fluctuates incredibly through the summer. It can be running like at 2,000 cubic feet per second (how we measure water volume in a river) one day and then after like a couple of days of hot weather, it can be down to 600, 500, 400 CFS. You wouldn't want to take your hard-sided boat down the John Day in September, when it's what river guides call "bony".

The North Fork of the Middle Fork of the Willamette (yeah, there are a couple forks in there) is a river that runs entirely on snow melt. And so oftentimes it just runs low in the summer.

Freestone rivers and blowouts

Glaciers don't only have ice. When a glacier melts into water, oftentimes there's a lot of stuff in there that the glacier picked up its prehistoric travels. Glacial remnants. All the chalky sediment that's been ground up as part of the glacier, and frozen in.

So when you get big runoff events—in the summer, or after a big rain—lots of sediment will come down, and make freestone rivers really mucky and dirty.

If you're ever fishing in the Deschutes River in Oregon, if you're ever steelhead fishing in the Deschutes in the summertime, you need to be careful because the White River, a tributary of the Deschutes, blows out. When it does, there can be so much glacial dust that Deschutes below where the White River enters (beneath Shearer's Falls) will turn milky and cloudy, and the fishing will slow down because fish won't be able see flies to eat them.

Here's what pretty extreme glacial melt discharge looks like, on the Etsch (Adige) river in the Italian Alps. This sediment kept the river colored up and un-fishable for miles and miles.

Food in freestone rivers is more variable and unpredictable than the other types of rivers we're going to talk about here, which is one reason why they tend to feature more variable feeders like smallmouth bass in their warmer, slower sections, and those populations seem to surpass trout in the summer months.

The John Day is really emblematic of this—there are a lot of smallmouth around during the height of summer. They thrive in freestone environments that are variable. The food is plentiful, but it favors an omnivore as opposed to more selective feeding fish like a trout.

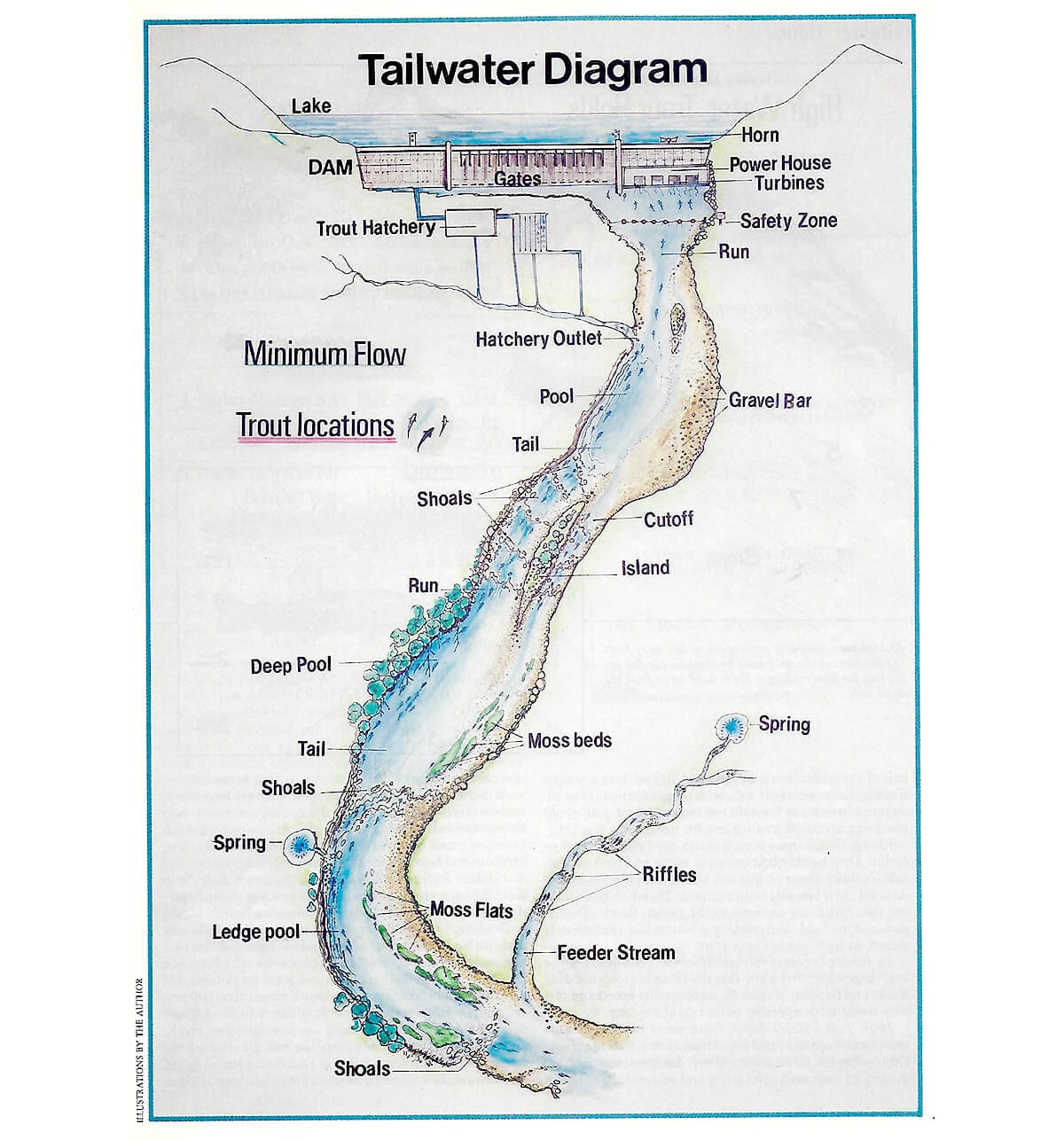

Tailwaters

A tailwater is different from a freestone river in that a tailwater is below a dam. So on the Crooked, a tributary to the Deschutes the best parts to fish are below Bowman dam.

In the lower 48 of the United States, we fish in a lot of tailwaters because we have a lot of dams. Nobody knows how many (shocking!) but it's somewhere north of 90,000. In Alaska, not as much: more free running, undammed freestone rivers.

In contrast to the variability of freestone rivers, on a tailwater you typically have reliably cold flows coming through the dam turbines from the coldest bottom water at the reservoir, year-round. Ahem, except for on the Deschutes, where they don't prioritize cold water...

If the people running the dam are doing their jobs right, the discharge from the dam, and the CFS of the river, is going to be predictable.

Tailwaters, especially right below a dam, are the easiest places to fly-fish because they're the most uniform, water-quality-wise. The steady cold water from the bottom of the dam creates conditions ideal for aquatic insect life. You get bugs that are able to live on the right microscopic plankton and algae and all the things that they eat. And that steady and consistent insect cycling across the calendar means the fish are able to grow big and happy.

Staying safe when you're fishing below a dam

Usually, in the western United States, you don't have to worry about dam releases. Since we don't get a lot of rain in the summer, dam flows are adjusted seasonally. Western water managers are consistent about drawdown.

In the East, however, dams can fill fast, and need to make more frequent releases. You have to be aware of a few things:

- Are there any planned dam releases while you'll be fishing?

- How will they be signaled?

- Is it at a certain time of day?

- Does a horn sound?

- What's your egress plan, to wade or walk to higher ground?

The magic of a double tailwater

Sometimes, you get a river that's been impounded at a lower juncture, and at an upper juncture, and that forms what we call a double tailwater. Think of it like the river that's left between two dams.

These are neat fisheries, and tend to be productive, because the reservoir conditions grow larger fish that then sometimes move up and down through the river section. And it's a fun little fishery because it's pretty stable and consistent.

One of my favorite double tailwaters is the Madison river, between Hebgen and Quake lakes, in Montana. Here's more on the phenomenon:

Spring creeks

Last, but not least, are spring creeks. A spring creek, as the name implies, is a river that originates in a spring. Usually in a pretty nondescript, subtle, creek-y way. With headwaters like a swampy seep area.

Sometimes, like the Metolius in Oregon, it just bubbles on up out of the ground and boom, you've got a river. If you go visit the Head of Metolius in Camp Sherman the river just starts, pushed up via a miracle of geology from an underwater aquifer way underneath the surface.

Spring creeks tend to be tricky to fish for a few reasons, mostly due to water clarity. The water's really clear because it's bubbling out of like the natural filtration of an aquifer, and isn't coming from sedimented glaciers or through the muck at the bottom of the dam, like in a tailwater. Spring creeks have the clearest water and the spookiest trout because there's not a lot of turbidity. There's not a lot of dissolved dirt debris. The fish, then, get really choosy. They have like a good diet of insects and they tend to be very particular and picky because they can see them clearly.

The Henry's Fork of the Snake River in Montana and Idaho is a big, wide spring creek. Also hard fishing. There are lot of rivers in the limestone-rich watersheds of Pennsylvania that are spring creeks.

Matching the hatch on a spring creek

Because of the water clarity and steady flow, spring creeks (and their choosy fish) tend to be the places where finding exactly the right fly to match the hatch comes into play.

They're the places where having exactly the right stage of fly (emerger, dun, spent, etc.) comes into play, in the right color, and the right size. And they're the places where it's most frustrating when you get a refusal, because you can usually see the fish come right up, inspect your fly, and head back to its hidey-hole when things aren't perfect.

Year-round fly-fishing on spring creeks

Spring creeks also tend to be open in the wintertime and flow predictably year round, since there aren't wintertime slowdowns for water storage, or when the water gets locked up at the summit in snow and ice.

The Metolius is a world class trout stream, maybe a little challenging for beginners, but at the same time very fun year-round.

The Clackamas watershed encompasses a few different river types along its watercourse, so it makes a good example, so we can learn more about the variation we're likely to encounter.

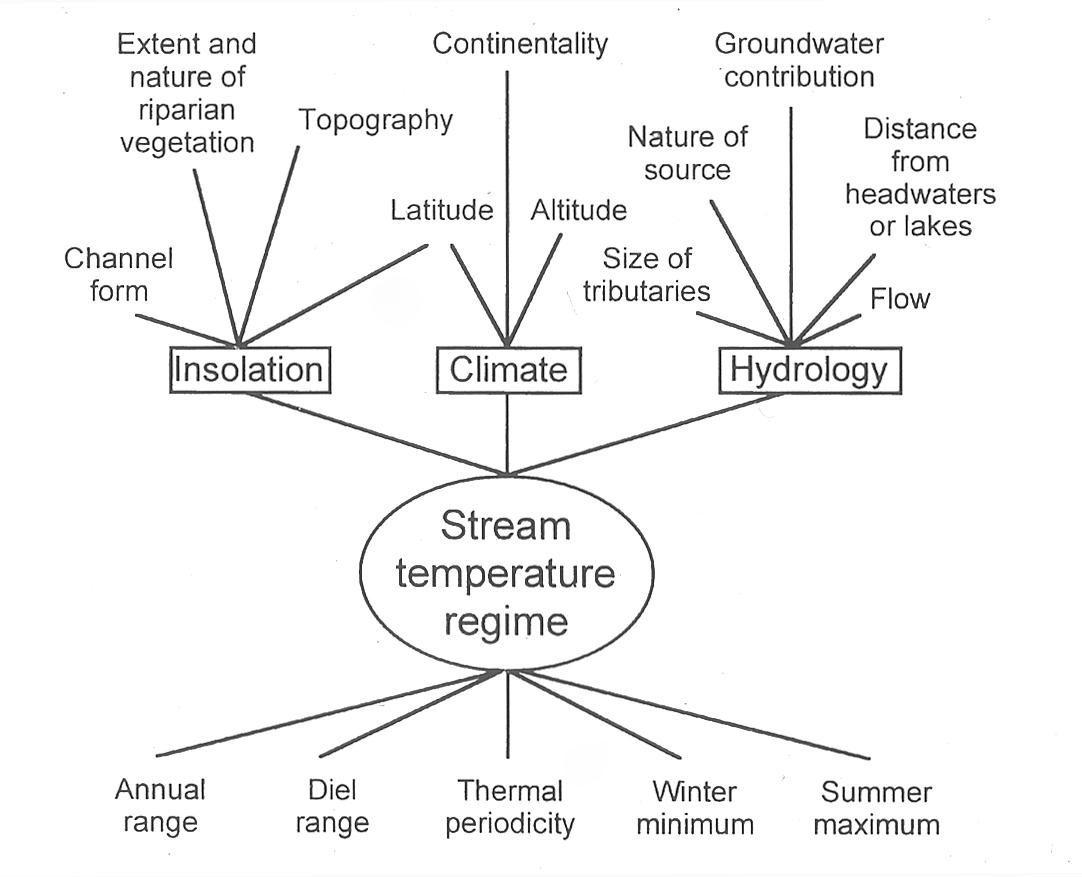

For a masters' degree in stream ecology

Visit The Living River, a compilation of materials from a 13-week course on stream ecology, created and collected by renowned microbiologist Dickson Despommier.

Spotlight on the Clackamas watershed

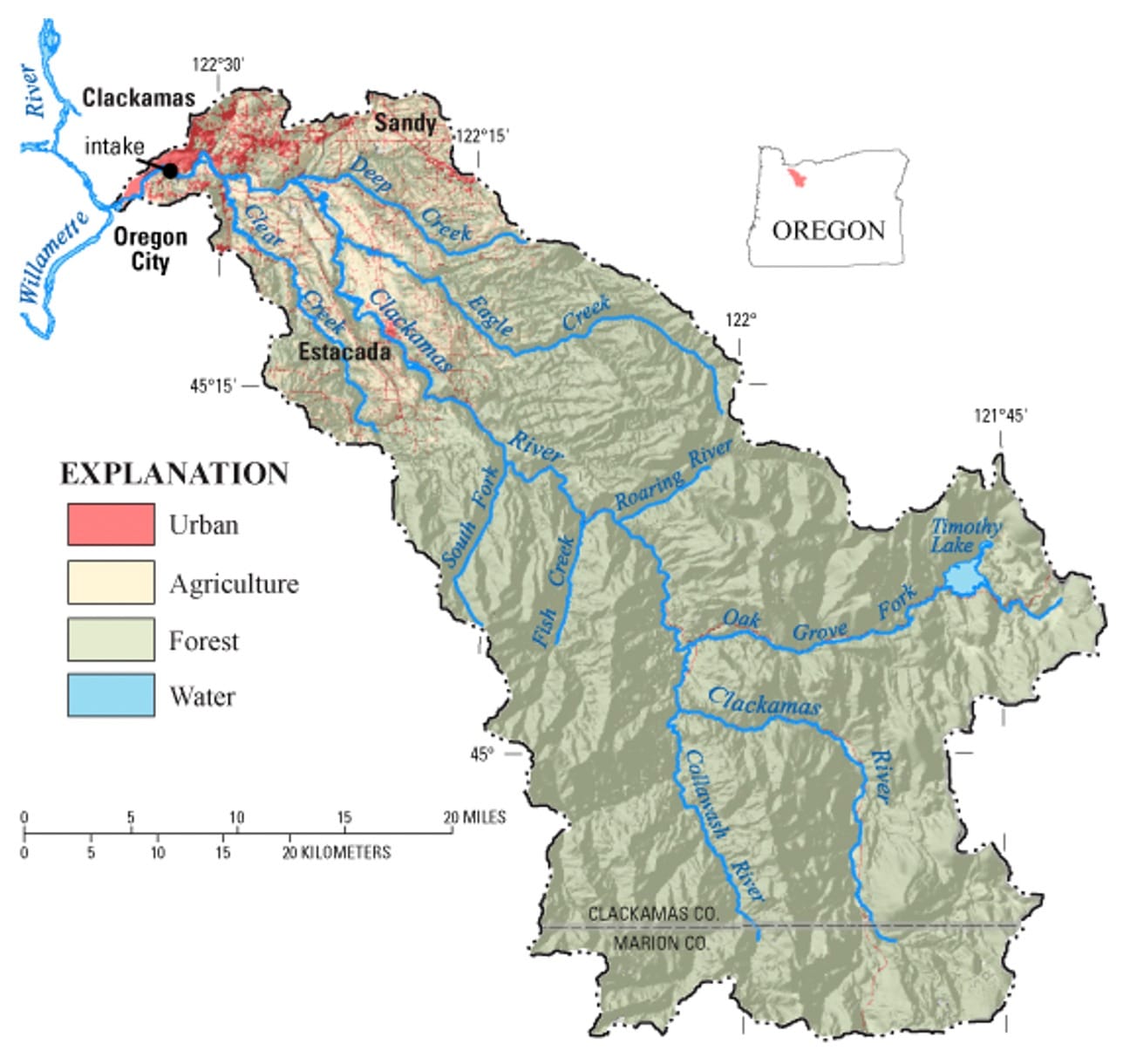

The Clackamas watershed is one of several that drain Mt. Hood in Oregon. (The others being Hood River, Bull Run / Sandy, and the White River / The Dalles.)

The Clackamas heads way up on the Warm Springs reservation, above Timothy Lake, and terminates at the Willamette in Gladstone. The Clackamas embodies multiple river types within one watershed.

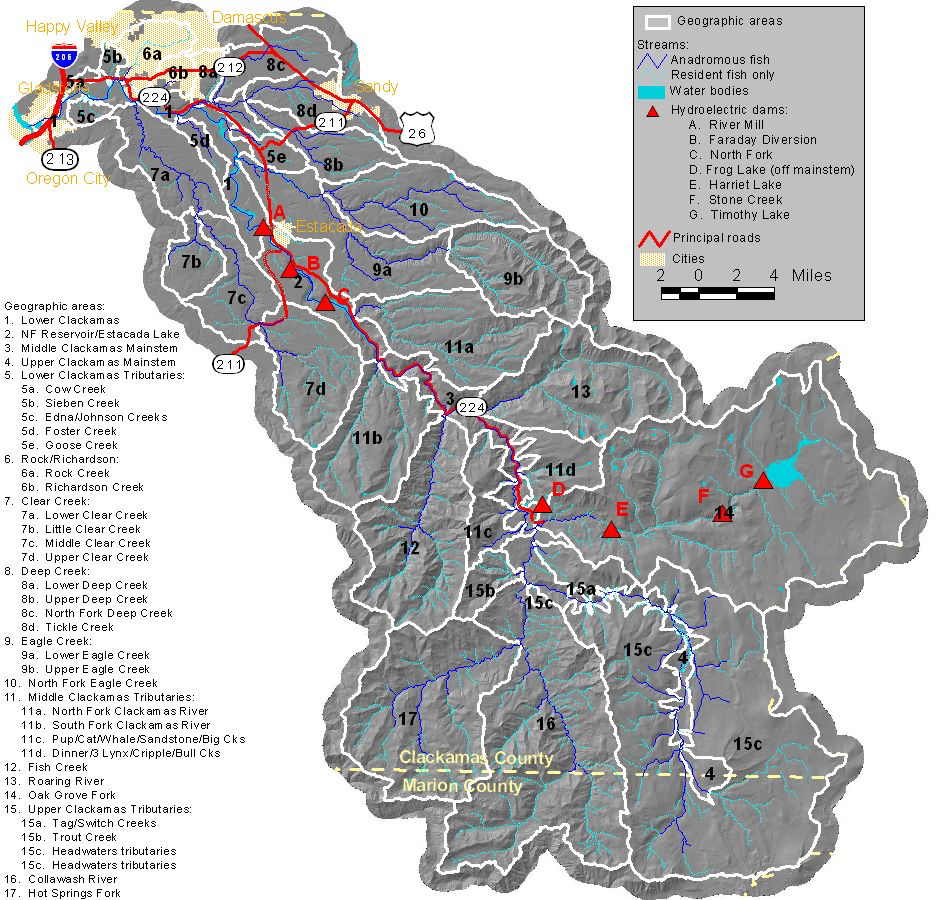

The Clackamas River is, through most of its course, a tailwater. Here's a map of all the impoundments on the Clackamas:

All those triangles are dams or impoundments of some sort, except for Stone Creek, which is a diversion dam, making the Clackamas a tailwater through much of the fishery. The Oak Grove Fork of the Clackamas comes out of Timothy Lake, held back by the dam.

The area between E, Lake Harriet, and G, Timothy Lake, make a double tailwater. And, in the tributaries above Timothy Lake, between the lake and the headwaters, you have alpine meadow style spring creeks, where the setting is a lot like this:

Summing up:

Before we zoom in further, to the actual topography of rivers, to where trout live, and the things they eat, it's worth taking a beat and doing a little bit of reflect.

Can you identify one of each in and around your home waters?

- a spring creek

- a tailwater

- a freestone stream

What are some nearby watersheds?

Once you've had a chance to do that, let's dig in further:

Understanding parts of a river:

Finding places to fly fish:

𓆟 𓆝 𓆟