From reel seat to tippet: understanding the anatomy of a fly-fishing rig

The knee bone connects to the thigh bone...the thigh bone connects to the hip bone...digging into all the things that attach to your fly rod, from reel seat to fly line to tippet.

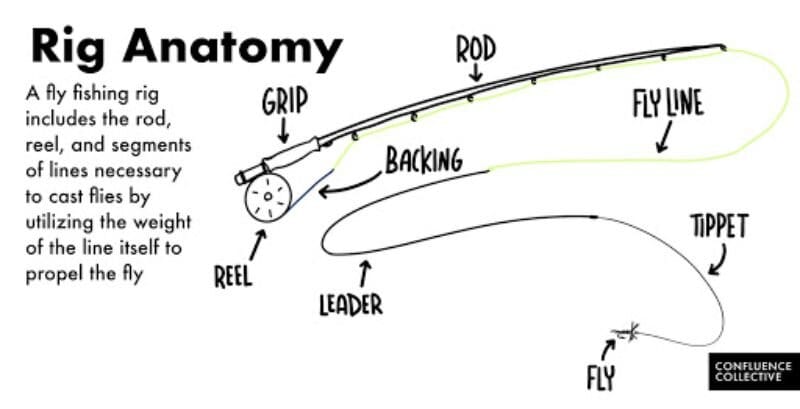

The anatomy of a fly-fishing rig

It's easiest to think of the complex connections that go through a fly-fishing rig like the old "Dem Bones" song we all learned as kids:

Toe bone connected to the foot bone

Foot bone connected to the heel bone

Heel bone connected to the ankle bone

From the reel seat ring at the very butt of the rig to the fly at the end, there are a lot of items to consider. And they're all, to the beginner's chagrin, held together by some different arcane formulas.

If you need a refresher on what holds it all together, don't hesitate to check back on our guide to knots:

Here's a great illustration on the overall anatomy of a rigged fly rod:

🚨🚨 Important to remember:🚨🚨

It's important to consider, as we go over this, that casting a fly is a transfer of energy from the caster's body, to the line, to the fly.

Our rigs transfer energy. That's their fundamental role.

The fly rod

There are a lot of variations in types of fly rods and reels you might want to use. You'll vary the setup based on the places you're fishing (are you in the ocean, or a big western river, or a small creek?) and the fish you're looking for (are you fishing for bonefish, or marlin? smallmouth bass, or walleye?)

Rod styles

The first place to start is with rods. Broadly speaking, you can divide fly rods into a couple different categories:

- Single-handed, most fly rods

- Two-handed, rods built for a growing subset of spey-style casting

- Tenkara, a traditional Japanese-style rod without a reel

Key rod facts:

- Most fly rods are between 7'-12' long.

- One-piece ("boat rods") exist too, but aren't very practical.

- They typically break down into 2-5 pieces, or, in the case of tenkara rods, have many sections that collapse into themselves down to 16" sections (perfect for a backpack).

Getting the appropriate size rod

For most beginners, a 9' 5wt is the ideal rod for most trout and general freshwater fly-fishing. It's the size of rod we recommend for your first fly rod.

But, as you explore more styles of fly-fishing, in more types of water, for different types of fish, you'll need bigger and smaller rods. Here's how those are typically considered.

(Bear in mind, with a lot of these very rational-seeming charts, there's wiggle room, and the divisions aren't cut-and-dry. Your rod won't blow up if you fish a 5wt for bass. Unless you hook into a really big fish.)

| Rod weight | Fly sizes | Species / style |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 8-2/0 | saltwater or steelhead |

| 8 | 10-1/0 | light salt, musky |

| 7 | 14-4 | bass, shad |

| 6 | 18-4 | heavy trout (windy, streamers) |

| 5 | 20-8 | go-anywhere trout, panfish |

| 4 | 22-10 | spring creeks, panfish |

| 3 | 24-10 | light trout, panfish |

| 2 | 24-14 | superfine, panfish |

Decoding a rod's info from its serial number

If you've already got a rod, maybe one you inherited, you will want to find out its specs, how long it is, what action it has. Somewhere on a rod (usually near the cork grip) you'll be able to find a model number that denotes length, weight, number of pieces, and action.

So, 90604F would be a 9', 6 weight, four-piece fast action rod.

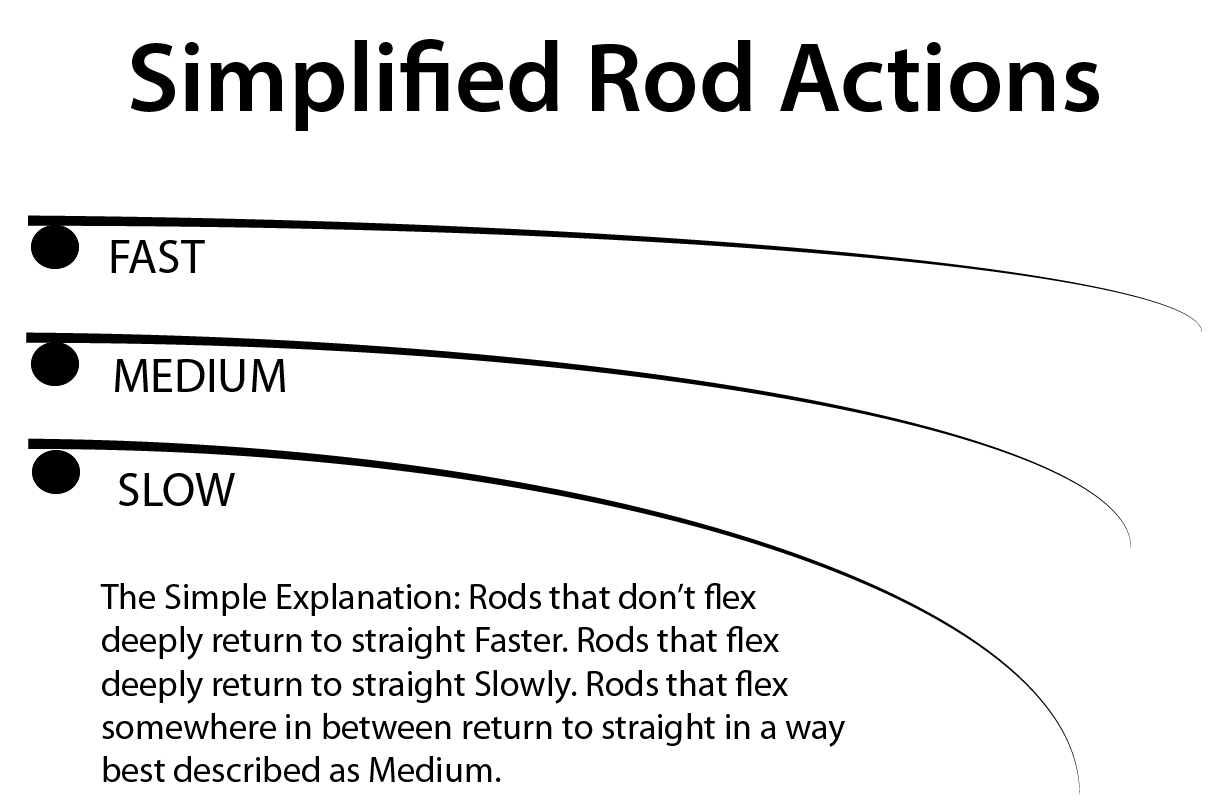

Rod action (How fast a rod returns to straight)

Most beginner rods are medium. Rods that are meant to cast heavier flies, such as streamers, are usually fast-action rods. Rods that are ment to be more sensitive, are typically slower action.

Materials influence rod action well. Graphite is faster than fiberglass which is faster than bamboo. Switching from one rod to another, from one material to another, will force you to change timing on your cast to adjust.

There's also slight variation in where the action is applied. Sometimes a fast-action rod is referred to as having "tip action" as the majority of the flex happens in the tip.

Actions, summarized:

- Fast rods: stiffer; back to straight faster.

- Slow rods = softer; back to straight slower.

- Certain materials are slower than others.

- Fiberglass & bamboo = soft materials.

- Graphite = fast and medium.

For further info on action:

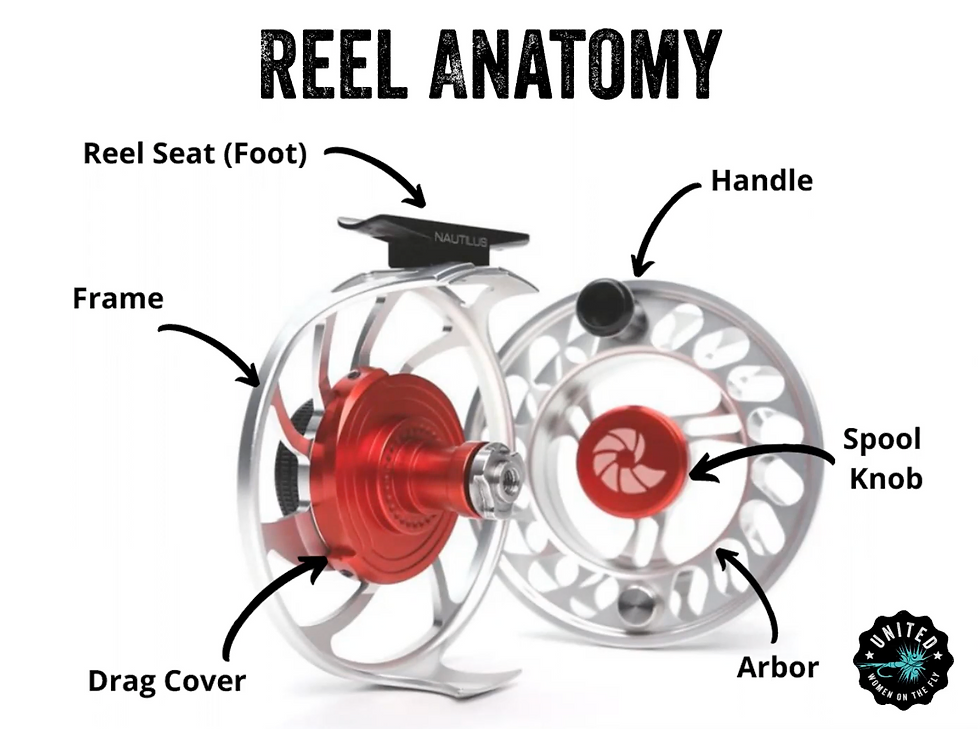

The next step on our chain of connection is to the reel. A modern fly reel has flanges on its base that slot into areas in the rod's reel seat, and then are tightened down with a threaded ring that adds tension. Check that tightness from time to time as you're fishing.

Fly-fishing reels

Here's a pretty good diagram of the parts of a fly-fishing reel from United Women on the Fly:

For most trout fishing, the reel's job is mainly to balance the rod and hold the line. You can land a moderately-sized fish by just stripping in line with your line hand and pinning it against the grip with your rod hand (while keeping your rod tip elevated at all times) to get the fish to your net and released quickly.

So the reel doesn't matter that much. Until it does. And you have a monster on the other end of it. Then, you'll need to use the reel's featuers to smoothly increase and decrease the amount of line on the water, and distance from the fish to your net.

There are mechanical advantages to a reel; typically most modern fly reels incorporate a drag system, that allows you to dial-up or dial-down the speed at which a fish can pull line out of the reel. With drag tightened all the way down, it's hard to pull line from the reel. With it loose, the spool spins easily.

Reels are sized in ranges to hold the right amount of a specific size of line. So, for instance, a reel for our hypothetical first-ever fly rod, a 5wt rod, can hold 4-6wt lines. So, if you get a slightly larger or smaller rod, you can use the same reel and swap out lines, or buy additional spools to hold your other lines.

The arbor of the reel, the spool at the center that rotates around the axle, is where the reel and the line interface, and a critical connection point.

For big, heavy rods, or two-handed spey rods that use thick, fat heads on the end of their running lines, you'll need a reel with a larger capacity, a bigger arbor (the ring in the reel that holds the line) to hold the line, and balance the size of the rod.

If you fish with a tenkara rod, you don't need a reel.

Backing, Fly Line, Leader, and Tippet

The multiple-segment, many material thing known as a "line" actually contains 3-4 different materials and diameters and each plays an important part. Next in our chain come our backing, fly line, leader, and tippet.

Backing

Backing is a dacron / nylon cord (think kite string) that connects your fly line to your reel. It is the insurance policy against a really, really (really!) big fish.

Most of the time, if you're fishing for trout, your backing will be set up when you buy your reel, spun onto the reel spool by someone in the shop with a cute machine, never to be worried about again. It really only comes into play when you're changing fly lines, which is why you want to make sure the shop ties a Bimini Twist or similar big-looped strong knot in the business end of your backing. That way it's easier to get fly lines on and off your backing, if you want to change from a floating line to a sinking line, for example, and don't have separate spools.

But, one day, you'll get a big fish on the line that wants to run. And the fish may take you into your backing. The main priorities in order to successfully play fish when they take you into your backing are to move your feet and maintain pressure. If the fish is running downstream, you have to follow. And, while you follow, reel up to keep pressure on the line and the hook in the fish's mouth.

Some anglers are comfortable playing big fish with a long amount of line out, and their backing exposed, but not me. I try to put the brakes on a fish like that and gain back some ground whenever possible. But, with the adrenaline and excitement of big fish, sometimes all bets are off.

If you ever need to replace your backing, or you've inherited a backing-less reel, some documentation that came with your reel should detail how much to put on. But the easiest thing to do is just take it to a fly shop and have them take care of it.

Fly line

Fly line is critical to help you load the road to make a fly-fishing cast. We've talked elsewhere about how what differentiates fly-fishing is the cast. Your arm moving in the cast and transferring energy through the rod, loading it, and sending the fly where you want it to go, is ultimately enabled by the weight of the fly line.

This is the difference between fly-fishing and gear fishing. In most elementary styles of fly fishing you don't have a heavy enough object (a lure) on the end of the line to be able to cast it with a flick of your wrist. (Mono rig proponents, we'll deal with you later.) Since accelerating the weight at the end of the line is out of the question, we have a thick plastic (polyvinylchloride or similar) line that is thicker in some sections than others, and use this to overcome air resistance and create the casting loop.

That's a lot. All you really need to understand is it's impossible to make a fly-fishing cast without a fly line.

Fly lines are measured in three ways:

- Size (how much does it weigh; chosen by rod match)

- Shape (what kind of taper does it have; chosen by fishing situation)

- Sink rate (does it sink? how much?; chosen by fishing situation)

Understanding fly line sizes

Size is meant to match the standard size of your fly rod. Really, we're referring to line weight. So, a 5-weight rod needs a 5-weight line. Fly-fishing standards bureaus maintained this classification for years, but it's since become a little roughshod.

Essentially, the weight of the first thirty feet of your fly line determines its size. There's a sub-measurement here, grain weight, an old measurement unit that once was for grains of wheat, and now is for bullets and fly lines.

Here's how that all translates:

| Line Weight | Grains (Low) | Grains (Target) | Grains (High) | Grams (Low) | Grams (Target) | Grams (High) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | 60 | 66 | 3.50 | 3.90 | 4.30 |

| 2 | 74 | 80 | 86 | 4.80 | 5.20 | 5.60 |

| 3 | 94 | 100 | 106 | 6.10 | 6.50 | 6.90 |

| 4 | 114 | 120 | 126 | 7.40 | 7.80 | 8.20 |

| 5 | 134 | 140 | 146 | 8.70 | 9.10 | 9.50 |

| 6 | 152 | 160 | 168 | 9.90 | 10.40 | 10.90 |

| 7 | 177 | 185 | 193 | 11.50 | 12.00 | 12.50 |

| 8 | 202 | 210 | 218 | 13.10 | 13.60 | 14.10 |

| 9 | 230 | 240 | 250 | 14.90 | 15.55 | 16.20 |

| 10 | 270 | 280 | 290 | 17.50 | 18.15 | 18.80 |

| 11 | 318 | 330 | 342 | 20.80 | 21.40 | 22.20 |

| 12 | 368 | 380 | 392 | 23.80 | 24.60 | 25.40 |

| 13 | 435 | 450 | 465 | 28.20 | 29.20 | 30.20 |

| 14 | 485 | 500 | 515 | 31.10 | 32.40 | 33.70 |

| 15 | 535 | 550 | 565 | 34.30 | 35.60 | 36.90 |

(n.b. if you ever find an old fly line and aren't sure what size it is, pop it on a metric-speaking kitchen scale and this should give you a pretty good idea.)

Grain weight becomes more important and widely used when you're dealing with two-handed rods, which often have multi-part lines. In spey fishing, you'll often have a flat, level running line, and affix a heavy shooting head onto that. More on shooting heads later.

Confused yet? Great. Any questions?

Can I use a different-sized line for my rod? My line is a 4-weight, and my rod is a 5-weight

Yes. Within about a one-size jump. This is called "overlining" and "underlining".

Primarily, you'll notice both in the cast.

A 4-weight rod with a 5-weight line will load faster than with a heavier 5-weight line. When we do our Intro to Fly-Fishing class casting, we overline the rods by one step to make it easier for beginner casters to feel what it's like to "put a bend in the rod," an essential noticing to being able to cast.

Underlining a rod is sometimes helpful to make more delicate presentations, or to get that "just right" feeling on a rod with slower action, like a bamboo or fiberglass rod.

You probably don't want to go more than 1 size, if you're stuck with an unmatched rod and line.

Understanding fly line shapes

Fly line shapes help perform an essential function in the physical performance of the cast.

Based on the distribution of the thickness of the line, or the taper, they require different amounts of force to form a loop that effectively turns over a fly.

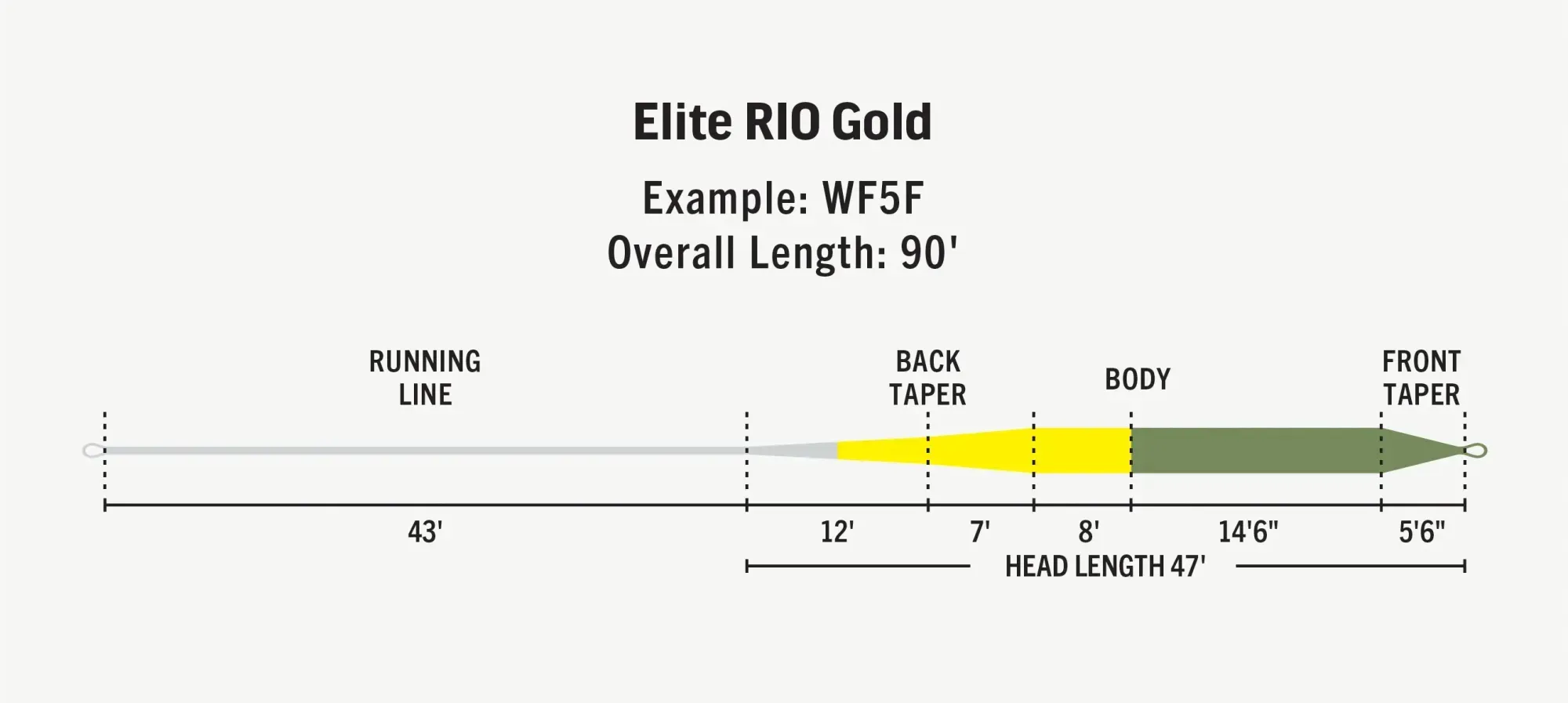

Here's a visual example of taper, with a weight-forward fly line:

The front taper area is the part that'll have the front loop, where you attach your leader, the running line area will terminate in a rear loop, where you'll attach your backing.

For most kinds of trout fishing, as a beginner, you'll want a weight-forward (WF) line, like the one pictured. Weight-forward lines turn the fly over easiest because the forward weight helps form a good loop. They are the most forgiving to to cast. Most of my trout fishing on 5 and 6 weight rods happens with a weight-forward line.

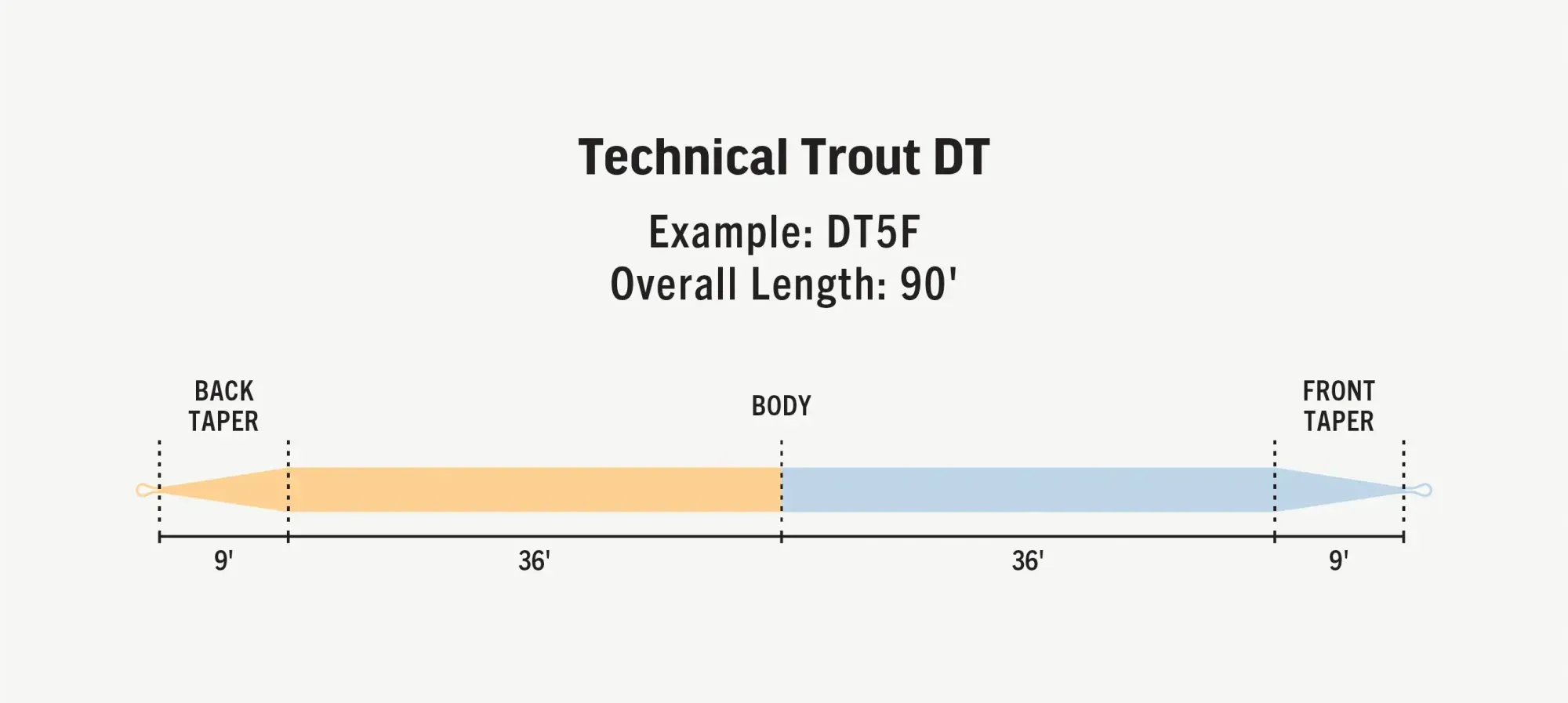

If I'm fishing a smaller rod, say a 3- or 4-weight, I use a double-taper line (DT). Here's a DT line profile:

You'll notice a couple differences to the WF line:

- The line is symmetrical. The back taper and front taper are the same.

- There's no exaggerated head.

Double tapers are used when you're in more delicate presentation moments, and need a longer leader to present the fly to spooky trout. That's why I use them with smaller rods. They require a little more casting precision, and reward less power and lighter strokes.

The symmetrical nature of double-taper lines means you essentially have two lines for the price of one. When the front taper wears out, gets grungy, loses its sheen, starts cracking, you can flip it around and use the less-worn back taper as the front.

(Another aside: Cleaning your fly lines is fast and easy and improves their performance and longevity. It's an essential maintenance step you should take every few times you fish.)

The other shape of line we want to talk about is a shooting head.

A shooting head or shooting taper is essentially the heavy front part of then weight-forward line, but detached. It's paired together with a tip, that attaches to its front section, about 10-20 feet of additional leader material that can float or sink at various rates, and running line, a level (no taper) long length of line that attaches to the backing, usually about 100'.

Typically these are used with two-handed rods, in situations where casting for distance is necessary, and you're likely to need 150-170' or so of total line, plus backing.

Leader

The leader is the second-to-last stage in the line journey, part of what's called "terminal tackle". It is tapered, gradually decreasing in size, and channels energy from the chunky fly line to the soft, thin tippet.

Depending on the fish you're fishing for, and flies you're using, you might use different types of leaders. For instance, I use a much different leader for smallmouth bass poppers than dry flies, because a big, fluffy popper does not fly through the air as efficiently as a tiny fly, so it needs a more stout leader to turn it over.

In the olden days (and, still, among the dollar-conscious and / or ultra-nerdy of us) people tied their own leaders, using blood knots to attach different diameters of tippet, according to leader formulas. Some leader formulas are near-canonical. This is another area of the sport where minutiae is rewarded. Check out, for example, LeaderCalc, to see all the different options you have.

As a beginner, you don't need to stress about all this, you can just buy tapered leader by the pack. Ultimately, if you find yourself wanting to do something different, you can. A leader is just a single, or various pieces of tippet, designed to effectively transfer energy from the line to the tippet.

Can I tie my flies directly to my tippet?

Yes, you can, but if you're using tapered leaders (more expensive than straight-up tippet) you'll eventually, after you get tangled and retie a few times, be into the tapering part of the leader, and the fatter leader might not fit through the hook eye on your fly. More on that in a bit.

Understanding leader sizing

Standard leader sizes are 7.5, 9, 12, and 15 feet. They go from 0X to 7X, same as tippet. The XX designates the tippet size, the fine end of the leader. Leader butts (the end that attaches to the tip of the fly line) are all pretty standard.

For instance, a Rio Powerflex 9' 5x trout leader (a pretty standard, multi-use leader) tapers down to 5x, or 0.006".

If you wanted to use this type of leader to fish dry flies, a common usage, you'd unroll it carefully from the package to avoid initial tangles or knots, stretch it by slowly pulling it apart to straighten it and remove any memory from the packaging, and add a section of tippet.

Tippet

The simplest way to understand tippet, then, is just an extension on your leader—more tip. It's usually tied with a double surgeon's loop to the end of the leader, in 12-18" lengths. If you're using an indicator and nymphing, your setup will get more elaborate. We'll discuss that in rigging terminal tackle later.

Tippet is the fly-fishing material you'll go through the most. You'll be breaking it and knotting it and cutting it and tangling it a lot. There are two types of tippet, monofilament and fluorocarbon.

- Monofilament tippet is nylon, it is hard.

- Fluorocarbon tippet is a polymer, it is softer, sinks more easily, and is more abrasion resistant.

I tend to use mono for most trout and bass fishing, except for nymphing. Most of the terminal tackle that goes subsurface when I'm nymphing is fluorocarbon. Same with saltwater fishing, I use fluorocarbon.

There are two major downsides with fluoro: It's way more expensive than mono, and it breaks down more slowly in the environment. Where monofilament takes 500 or so years to break down, fluorocarbon takes 5,000.

So, be sure to dispose of your extra bits of tippet and leader effectively. Wad 'em up in a pocket, dump them in a little cup. They will be around for a long time.

Putting it all together: Matching tippet and fly size to your target species, water, flies, and rod

Almost there. You're ready to tie a fly onto the tippet. But, a big size 1/0 Clouser Minnow will break off a 7X piece of tippet as you try to cast it, and you won't be able to get a 3x tippet end through the hook eye of a size 22 Griffith's Gnat.

Remember back to the beginning, where we chose the size of rod we'd want based on the fishing situation? We're doing that same thing again. You have to match your tippet size to the flies you're going to use, and the fish you're going to be trying to catch.

My shorthand is to start backward from the type of fish you're trying to catch, to the kind of water you're in, then the type of fly you're going to use.

Don't worry: this will become intuitive before long, and you'll reuse the same formulas / setups if you fish in the same way in different places.

So, take this chart for instance:

| Tippet size | Hook / fly size | Tippet diameter | Breaking strength (lbs) | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0X | 1/0-4 | 0.012 | 15-15.5 | Salmon, steelhead |

| 1X | 2-6 | 0.01 | 13-13.5 | Bonefish, redfish, permit |

| 2X | 6-10 | 0.009 | 10-11.5 | Bass, largemouth and smallmouth |

| 3X | 10-14 | 0.008 | 8.25 | Bass and large trout |

| 4X | 12-16 | 0.007 | 6-6.4 | Trout |

| 5X | 14-18 | 0.006 | 4.75-5 | Trout and panfish |

| 6X | 16-22 | 0.005 | 3.4-3.5 | Trout and panfish |

| 7X | 20-26 | 0.004 | 2.4-2.5 | Trout and panfish |

| 8X | 24-28 | 0.003 | 1.5-1.75 | Trout and panfish |

Let's say we're going to fish for trout. We'll probably be good with a leader and tippet anywhere from 3x to 7x.

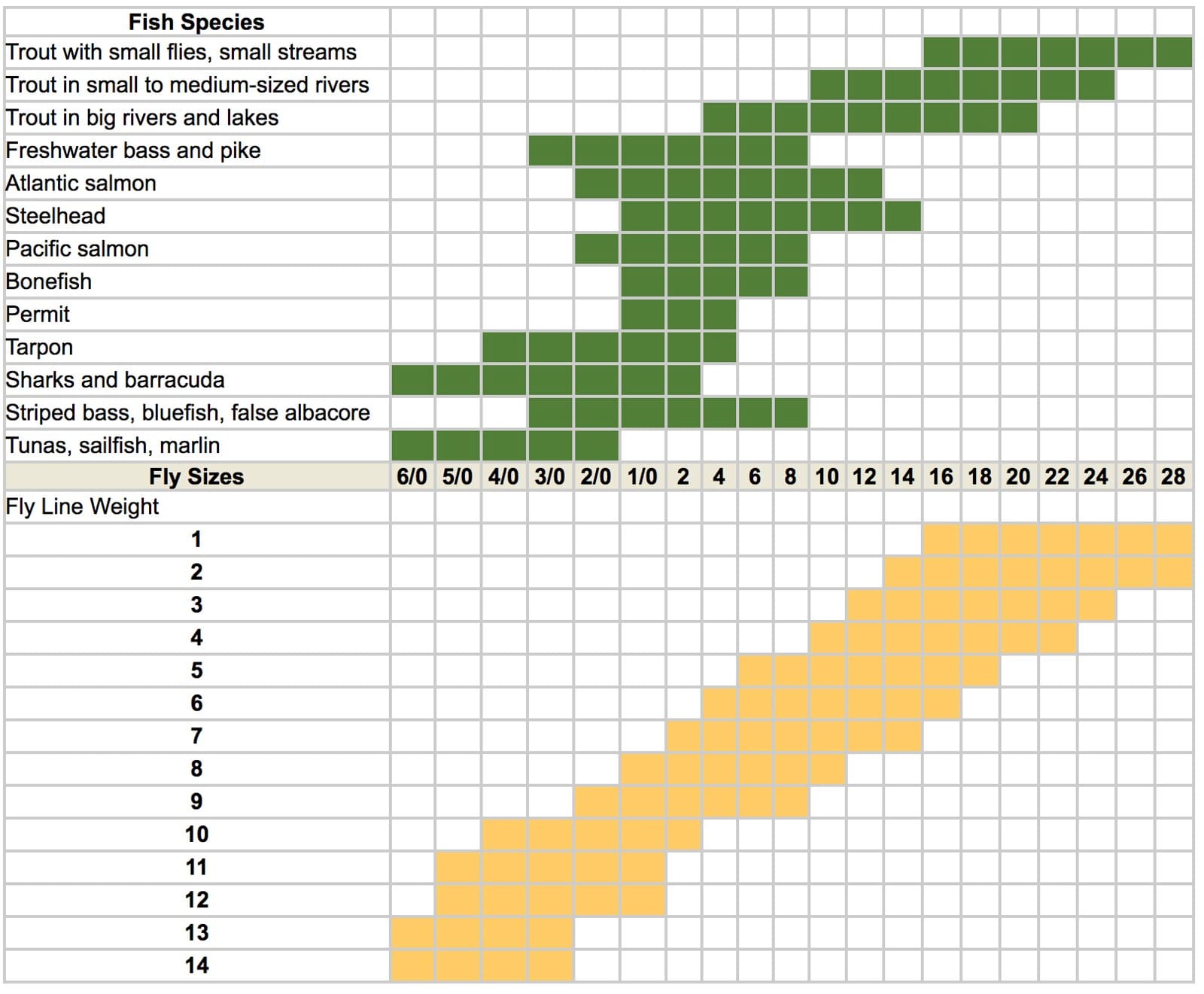

Then, we might check out this chart. We're going to be on the Metolius, a medium-sized river, using flies in the size 12-18 range. That tells us a line weight (and rod weight) of 3-5 would do the job.

That's it!

It may seem a little imposing at first, but experiment a little and get a few outings and spots under your wading belt and things will become more clear.

Questions?

Put 'em in the comments.

𓆟 𓆝 𓆟