Fly-Fishing in the Italian Alps, Part 2: Blowouts, high water, and mystery trout on the Swiss border

Can you help identify this strange trout variant? Salmo truta helvetica?

It’s the most wonderful time of the year here in Oregon, as the weather cools and all sorts of fish get more active. Steelhead are pushing up the Deschutes, coho are in the Clackamas, and sea-run cutthroat abound at the coast. I hope you’re enjoying the changing seasons and getting some time in on the water.

Before we get to fall, though, here’s a flashback to last month’s Italian adventure, this in the north east part of the country, Trentino-Alto Adige / Südtirol. If you missed Part 1, all about the rules and regulations around Italian fly fishing, you can find it here.

n.b. If you're reading this and have expertise around fly fishing in Italy that would be helpful, or you can correct any of my likely plentiful errors, please leave a comment!

Big nymphing

By the time we got into our third week of vacation, I had managed to sneak away from the family five or six times, enough to start to figure out trout fishing in Italy. Or so I thought.

Across Piedmont, and now in Trentino-Alto Adige / Südtirol, I’d found success with techniques that were first devised there many years ago, but now common worldwide: nymphing, tight-line Euro-style, occasionally under a suspender. (That’s a classy way to say bobber, though the New Zealand wool system was the most effective.)

I prefer fishing dry flies. Doesn’t everyone? We were mostly in crystal-clear water, where big trout held in knee-deep pockets. Fantasizing about topwater takes as I rigged up one morning made me lose concentration enough to blow tying the simple clinch knot three times.

But with a few notable exceptions, fish on the larger rivers stubbornly refused to rise to dry flies. It was excruciating. Whether this was common, or a reaction to the heat of summer, I never found out. Like a lot of stuff in Europe, things appearing similar to the U.S. contain nuance to discover.

But then there were smaller rivers. And an intervention from Mother Nature.

The Mother of All Blowouts

Let's start several days earlier, in the town of Merano. I was talking with the proprietor of Jawag, a hunting and fishing store that serves as the permit warden for the stretch of the Passer river outside of town that I had fished a few days prior.

In returning my Passer ticket we were doing a bit of a debrief, and I mentioned we were heading up toward Stelvio and spending our last few days in a mountain town called Sulden. I wanted to fish the Etsch (Adige), another famed river with a lot of beats seemingly on offer. He tut-tutted a bit, looking for the words, and then between his decent English, my bad Italian (”é molto turbido?”) and his native German we arrived at an understanding: There’s a big-ass glacier at Sulden that pukes concrete milkshake of glacial silt and sediment into the Adige, and anything below that is unfishable until temps drop and the glacier freezes again. Sort of like the relationship between the White river and the Deschutes in Oregon, but turbocharged.

Indeed he was right. And a few days later, in Sulden, I found the exact source of the turbidity that persists hundreds of kilometers downstream. At least one of them, anyway: The second-largest glacier in the Trentino-Alto Adige region, Vendretta di Solda, smack dab between the Ortler and Gran Zebrù peaks, getting smaller and smaller each year as temperatures rise.

This was the view up from the suspension bridge below, as a massive load of glacial sediments cascade down the mountainside.

Swiss neutrality saves the day

After checking things out I brought my puzzle to the altar of a local cafe in Sulden. Over a macchiato, then a Negroni mezcal, I realized there was only a single option on the Flyfishing Meran site that fit my criteria of:

- Within an hour’s drive

- Day passes available (and sold by an establishment that was open on a Monday)

- Didn’t touch the filthy Sulden

It was the Ram (or Rambach in German), a river that forms near the Forno Pass where the Engadin valley and Val Müstair abut.

And you can add a third name for this river: Rom, in Romansch, the language variant spoken in Grisons, the Swiss canton where the river originates. Our first Swiss river. And, as far as I could tell, this one should have far less glacial sediment.

But then the weather turned. We got two inches of rain the day before I was meant to fish, our last day in town.

"Shoulda been here yesterday" is usually reserved for consoling anglers when the bite is off. But this time I found myself thinking it as I took at look at the river on the way back from buying my pass at a pizza joint in Glurns.

How long will it take for the river to clear? Could I fish it the next day?

At least I knew it wouldn’t have to be an early morning. The longer I waited, now that the rain had stopped, the lower the water would get. I slept in, had a huge breakfast at the hotel, lazed around a bit, and then headed out around midday.

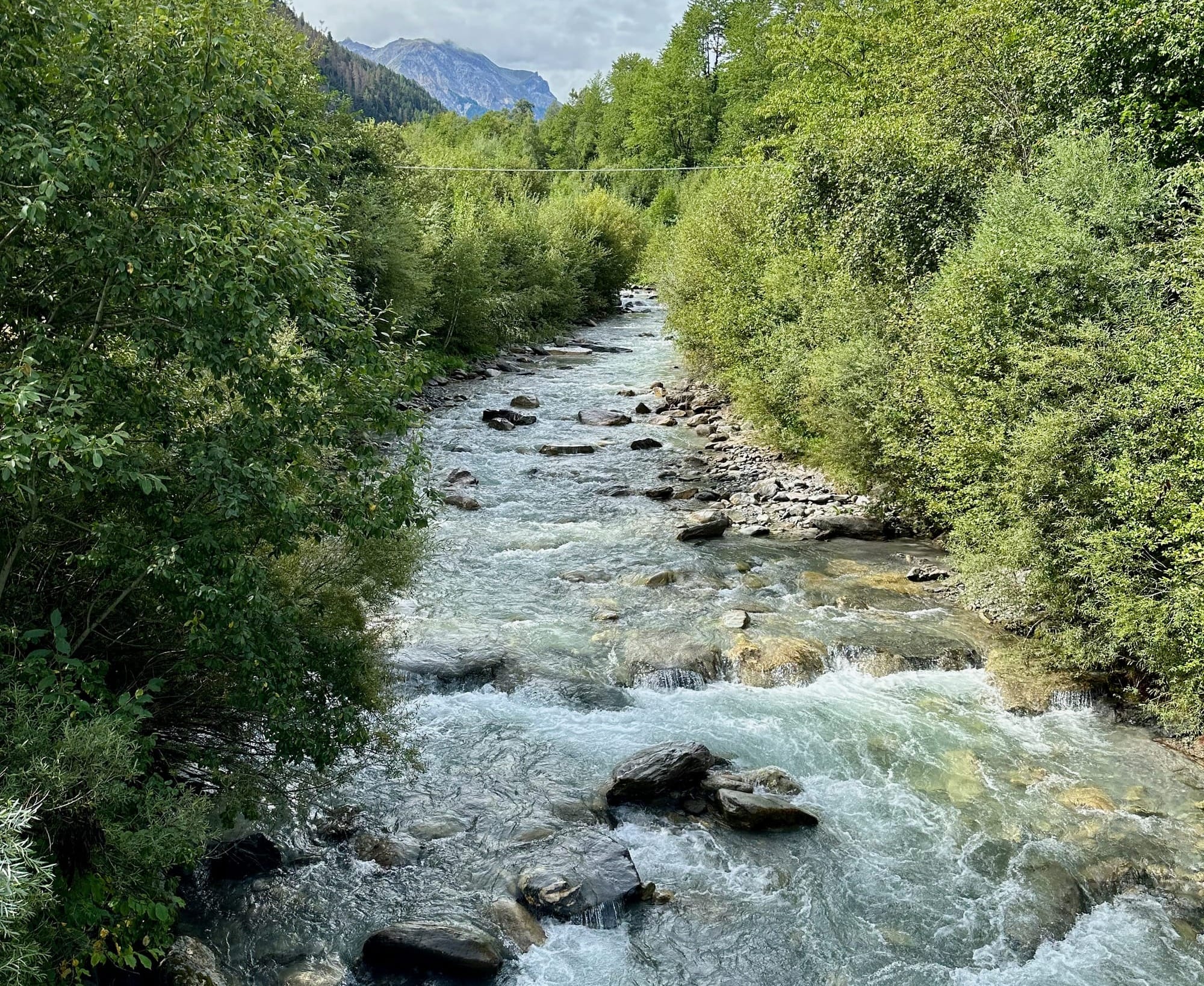

I started halfway up the beat, in the village of Rifair, headed toward the deadline at Calvenbrücke / Ponte Calven. My thinking was, the further up, the clearer the river would be.

The difference of a mile or two upstream didn’t matter all that much. But thankfully the river was much clearer than the day before. I could see the bottom near the edges. That’ll fish.

I parked at a handy map / information board, which are ubiquitous around walking tracks in the area. It explained a little more about the river:

The Ram originates at Ischiery below the Passo del Forno. As a powerful source, it emerges there over impermeable Verrucano layers. The water first seeps into the gypsum-containing limestone. The Ram is the only major stream in Switzerland that is not used to generate electricity.

After 17 km it flows across the border at Müstair/Taufers in the Münstertal. Five kilometers further, the Ram, as it is now called, flows into the Adige near Glurns.

In South Tyrol, the Ram is one of the few rivers that have not yet been exploited.

There’s even a little poem:

I set off up a trail that hadn’t seen maintenance in a few decades and quickly came to a river with rocky, riffled character, with plenty of room to run nymphs through what felt like promising stretches. Trouble was, I couldn’t find any fish in the usual places.

I got my first clue about an hour into the session, when the boulders and trees began to thicken on the banks and the river came over a natural spillway. I noticed on both edges of the spillway there was a tiny backeddy that had formed, which contained just enough foam to catch the eye. And, lo and behold in that foam—tiny mayflies.

That was the secret to the Ram, at this water level. Finding the tiny backeddies and pockets where fish could hold out of the main current. It seemed not only did the fish get respite from the push, but nymphs collected and hatched, so the trout had excellent lies.

Once I figured that out, I started catching, so much so that I kicked myself for not seeing all these little pockets earlier as the valley closed in on the river and the banks became steep and boulder-defined.

It seemed slightly possible marble trout might inhabit this relative trickle, so I was still optimistic I’d be able to check a marmorata off my list before the trip was over.

Alas, it was not meant to be, but amid the browns I found a few mystery trout with coloration I hadn’t seen before, a very large spotting over light sides, with very few red spots like the browns I had been catching.

Salmo trutta lacustris? Or just regular browns? Note the tiny red spotting near the pelvic fin on these specimens.

Later on, I tried to identify them with the Bolzano region’s fish ID brochure (picked up at its cool office on my trip to get a license). The brochure seemed to suggest they were lake trout (Seeforelle / Trota lacustre), which is surprising.

One hypothesis I thought through was the recent high-water episode had washed them down, but checking a map later (and translating the info board) its clear there isn’t any impoundment above the stretch I was fishing.

This paper refers to salmo trutta lacustris as a migratory brown trout, so perhaps that's what they are, but it's unclear where to / from they migrate in this case.

So, the mystery remains. What were lake trout doing in a river this shallow? Is this common? Are they perhaps a hybrid brown? Are they just brown trout without a suntan? Let me know!

I hopped up from run to run now, fishing the boulder-strewn stream as I would a spring creek, looking for those foam dots, then running my nymphs through a couple times. If there was a fish there, it wouldn’t delay.

One larger fish left its hiding spot and charged my nymphs down, then broke chase when the nymph dragged. The fish then held right where it broke chase, in clear open water, letting me take another shot. Again, it followed, but I couldn't get a drag-free drift longer than a few feet before it turned away and held a few feet below. At the bottom of the pool I connected on my final shot, only to have it shake the fly off after to dove over a cascade down into the next pool.

I caught a few more fish in the eddies, then spied a farmyard that indicated I had reached Puntweil, the little village with the Calven's bridge, where the beat ended.

Realizing I was famished, and hadn’t had a sip of water in three or four hours, I walked up to the main road and 100m across the Swiss border.

I set my net and fly rod down outside a Denner Express and picked up a Swiss lunch: a chicken curry sandwich and a bottle of Rivella.

I should have probably gotten a milkshake, to toast both the success in weird water conditions and my first multinational fishing session, but I figured the Rivella had all the turbidity I wanted for today.

A quick walk across the border to re-up and rehydrate, then back down the mountain lane to Rifair.

What do you think?

- Have you fished in Italy?

- Have you fished in Switzerland?

- Reply, or let me know in the comments.

In the next few installments of the Fly fishing in the Italian Alps series I'll continue to share specifics on places I went and rivers I fished in Trentino-Alto Adige / Südtirol and Piemonte, so stay tuned.