Read By the River: James C. Scott's In Praise of Floods

Saving dolphins, propitiating river spirits, and the future of history

We kicked off our Read by the River book club last week with a discussion of esteemed Yale sociologist James C. Scott's In Praise of Floods.

Was the book directly related to fly-fishing? Not exactly. But the discussion came back to angling lickety-split, as In Praise of Floods touches on the essential elements of riparian (river-related) ecosystems. Of which—spoiler alert—floods are one.

Scott's other works

Several members of the discussion group had read Scott's other published work, which slants toward what you could describe to explorations of anthropological anarchism. Several had read one or both of his best known works. Both of which concern engineering and control of natural modes of being, a theme in Floods. Against the Grain looks at how domesticating cereal crops and organized agriculture led to the rise of the modern state. Seeing Like a State analyzes several major efforts to quantify reality for state control, and how they didn't quite work out.

Scott mentions both in Floods, and also key elements of another of his books, The Art of Not Being Governed, an earned medley from an author and thinker who's long-since established a Greatest Hits of ideas.

Mission of Burma

The book's thesis spans watersheds and rivers around the globe—the Yellow River in China, the Mississippi in North America, the Nile in Africa—but its central character is the Ayeyarwady, a river that runs like a central nervous system across Burma.

The book has tinges of melancholy, not just for the negative issues that have caused flora and fauna—in the Ayeyarwady and worldwide—to decline at a precipitous rate.

Scott—who died in last July at 87—was clearly both passionate about the country, and unable, due to its present political inaccessibility and his advanced age at the time of writing the book, to visit.

Counter-currents of thought

For a few readers the core of the book was counter to received wisdom. Scott's perspective questions our broad system of "management" of rivers, asserting a river is a living, changing system and any alteration by human efforts, any anthropogenic change, isn't necessarily good.

We take for granted engineering projects that dam and control rivers, and efforts to build dikes and levees to control floods. Human-authored progress is generally accepted as good. But, as Scott shows, it isn't always, and often carries more cost than benefit. Certainly for the myriad creatures that call the river home.

And, on a long enough time scale, the river always wins. Sediment load is a perpetual effect of damming a river, for instance. As a result, dams across the world have a perpetual bank of sediment building behind them, reducing their effectiveness.

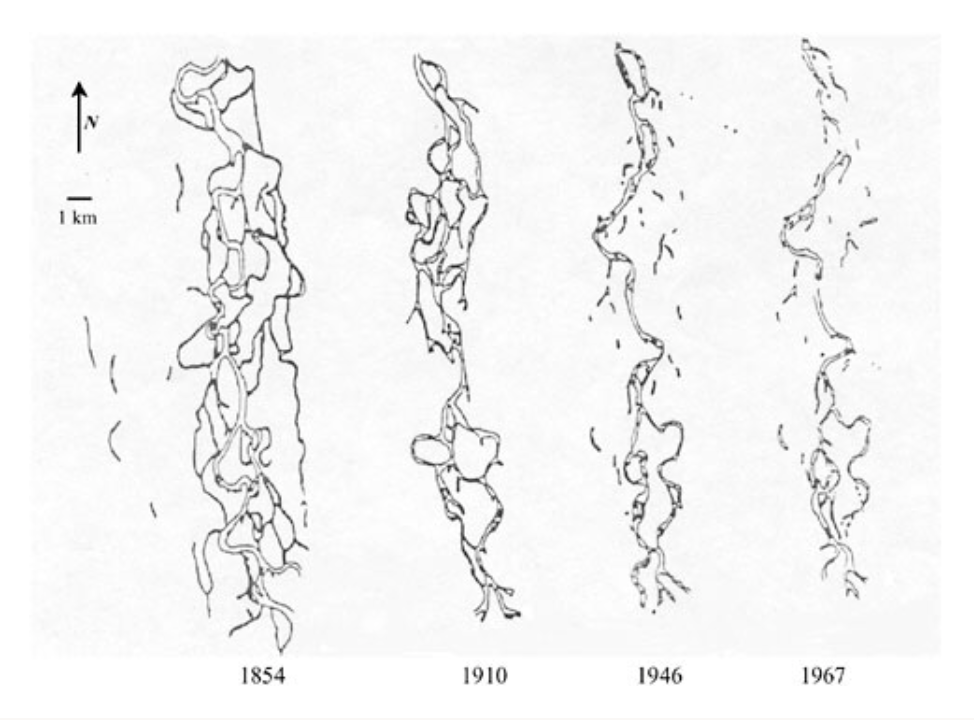

Robert shared this study of the changes in Oregon's Willamette river:

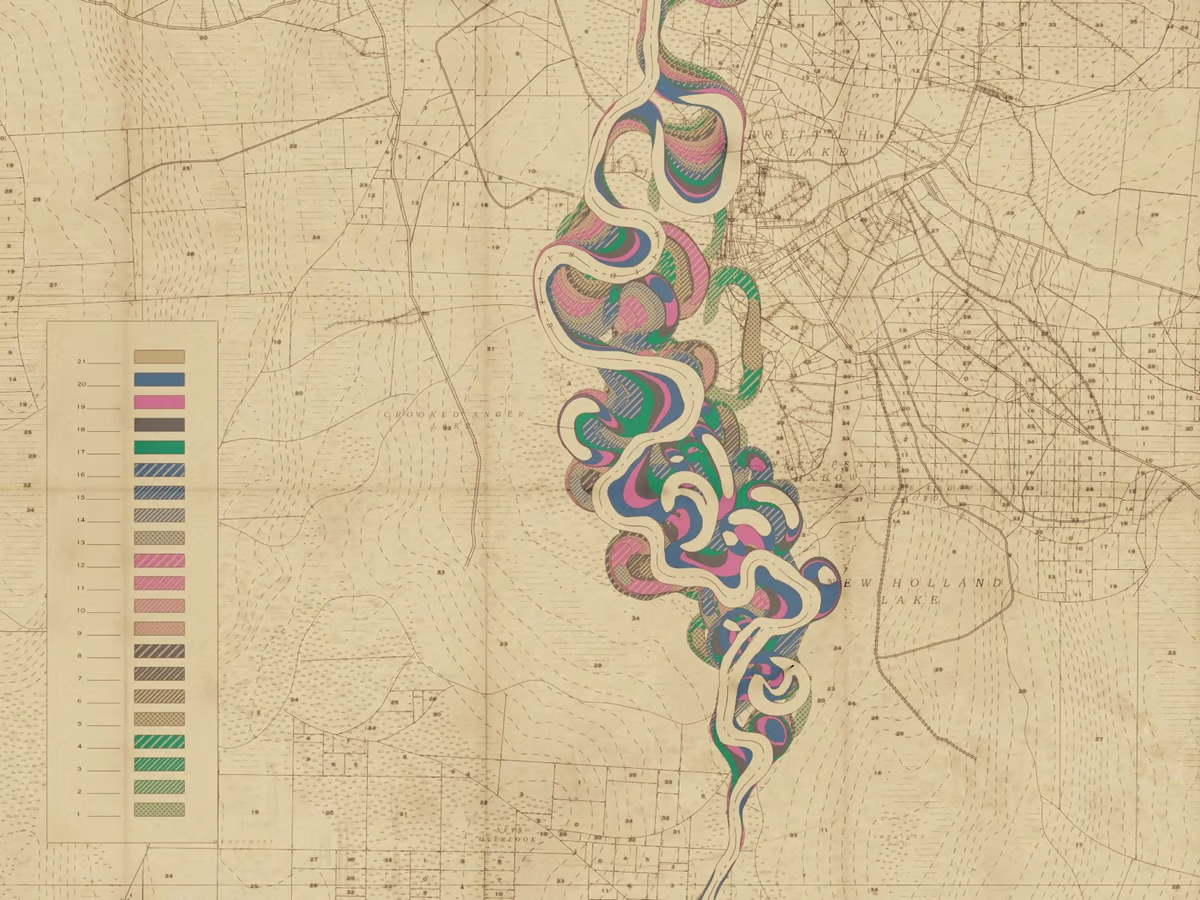

And Graydon showed his prints of artist Robert Hodgin's imaginary meander maps:

As one YouTube wag pointed out in this exceptional study of sediment load and dams, "much like retaining walls there are three kinds of dams; those that are falling down, those that have fallen down, and those that will fall down. Most people fail to understand the gravity of the situation."

A multi-modal grab bag

One criticism of the book the group levied is it feels like a bit of a grab bag, without the strongest sense of narrative conveyance across the chapters. This, we agreed, can be excused. The material inside In Praise of Floods was clearly gathered over the course of many years of experience, and

One delight in the narrative are two side-channels considering other entities inside the Ayeyarwady system. One chapter, co-authored by two Burmese collaborators, goes deep into the local spirituality around nats, river spirits that local people propitiate in hopes of bringing their good fortune as they travel, fish, and

And so we offer a small side-excursion, In Praise of Nats:

The other narrative excursion travels alongside the non-human creatures that ply their trade in the watershed. It's guided by the lovable Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris), a lovable creature who introduces other river-users humans might have overlooked. The impacts of anthropogenic changes on these creatures habitat and how they've coped (another spoiler alert, they're in trouble) is a pleasant break from the more quantitative geological elements Scott portrays in earlier chapters.

Acknowledging these living beings feels important, and something we can bring home. My gardening mentor, when she collects blooms and flowers from plants, or harvests mushrooms, always says "please" and "thank you". Another book club participant described a person who exchanges special rocks with stories whenever they take compost from a communal pile for their garden.

This kind of soft animism feels like a gentle way of acknowledging our relationship with the natural world that goes beyond pure utility.

History keeps happening

The book does a great job in explaining how river topography changes over time, altering not just the physical boundaries of a river in its banks and watercourse, but also the political boundaries, of villages and claimed territories.

Similarly, it creates a strong impression around the idea that history keeps happening, and we continue to learn more about the past that changes our relationship to it.

This is most evident on a float trip with a guide who sees a river periodically, across a season, over a series of seasons. They'll point out the effects of high water and erosion and material in the river like trees and debris creating new channels, varied meanders, and the alterations in an ecosystem a river creates in its constant mutation.

I think a lot about the parallels between surfing and fly-fishing, and this is one area where they differ. While surfing sometimes requires more observation and understanding of the ocean and its forces, and how terrain and wind and waves combine to form breaks, those breaks are relatively constant, whereas inside a river, the general character is slow to change, but high-water events may scour out areas that previously held fish, or bring new ones into play.

Closer to home, on a far longer timescale, the geologic history of the Columbia and the changes its wrought on the landscape of the Pacific North West came up. Scientists are still discovering new wrinkles to the unique history of the places we inhabit.

Troubles both anthropogenic and iatrogenic

Lastly, what is to be said for the pain and pessimism that pervades any serious study on human impact and the outdoors? Our way of being causes serious, permanent trouble for the planet, and it can be sorrowful to acknowledge. Our attempts to fix or correct or repair sometimes cause more harm then good.

Scott describes these in his final chapter, dubbing them iatrogenic effects, related to the use of the term to describe sickness or impairment caused by medical treatment.

Beyond structural changes, re-introduced species raise questions about what is native, and what is invasive, and whether the removal of latter organisms for the benefit of the former is always the right thing to do.

Complicating things further, we have to overcome the belief that inaction, or non-action, can be written off as natural. The famous Love and Rockets line states it plainly: "you cannot go against nature. Because when you do. Go against nature. It's part of nature, too." But, lately, that feels more like a cop-out, a rationale for the status quo, which is untenable in the current environmental crises we find outselves having to build new thinking to outwit.

Join the next Read by the River discussion

Thanks again to everyone who joined. Thanks, Graydon, for suggesting the book!

I'm hoping to host these discussions every few months. Stay tuned to the newsletter for the next announcement.

Got a nomination for a book the group might want to read? Let me know!